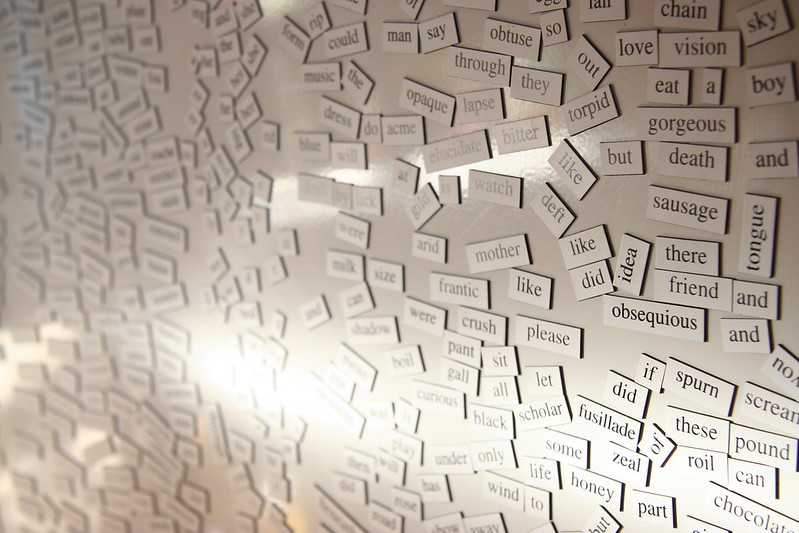

In a world where convenience is key, everything is susceptible to shortening, hurrying, and simplifying even at the expense of the quality of what is being presented.

Language is no different–while many may argue that shorthand and slang are reflective of new times, abbreviations have been found in ancient Greek manuscripts and acronyms have been used since 1879. Abbreviations and acronyms continue to be a significant part of expression through language and have generally made lives easier when there seems to be so much to say yet so little space to say it.

The problem begins when people start to use abbreviations and acronyms without the knowledge or understanding of the actual meaning they refer to. It may seem harmless enough when it comes to grandparents misusing LOL as “lots of love” instead of “laugh out loud,” but in other contexts, this reliance on abbreviations and acronyms poses further complications. As we have begun to rely heavily on taking shortcuts when it comes to describing and identifying people, these complications have started to surface in things such as community labels. While our growing bag of acronyms seems convenient for quickly bringing different groups of people together, it also becomes easier to bypass learning about each individual part included within an umbrella term.

The Asian American community has become one of the most labeled communities within the last decade–from the racist “Oriental” to the rise of the term “Asian American” out of the Asian American Movement in the 1960s, to the more recent APIDA (Asian Pacific Islander Desi American) acronym, these umbrella terms continue to be an integral part when speaking about the community.

The term “Asian American” is credited to activists Yuji Ichioka and Emma Gee, created in 1968 during the founding of the Asian American Political Alliance. The creation of “Asian American” was a direct response to the once popular term “Oriental” to describe people of Asian descent and appearance, and was a product of the Asian American Movement’s emphasis on panethnic solidarity and self-determination. By identifying as “Asian American” during this time, one would make a statement about identity as a person of Asian descent.

Nowadays, the term has primarily become a demographic marker. It has lost its radical meaning over time and has become a shortcut to group all Asian ethnicities into one box.

In the words of Charlie Chin, best known for his participation in the Asian American music album A Grain of Sand, “Currently when you say Asian American, all it means is that you are of Asian descent. But originally, it was a loaded word, an explosive phrase that defined a position, a very important position: I am not a marginalized person. I don’t apologize for being Asian. I start with the premise that we have a long and involved history here of participation and contribution and I have a right to be here.”

The evolution of the term “Asian American” is a testament to how easy it is for the general public to pick up abbreviations and acronyms without knowledge of their deeper meaning. Not to mention the convenience of not researching further into the groups of people that have identified within the community of “Asian Americans.”

Since the initial creation of “Asian American,” the term has expanded into a number of different acronyms–the public has used the term AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander), APIDA (Asian Pacific Islander Desi American), AANHPI (Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander), and everything in between.

The growth of acronyms and umbrella terms is a double-edged sword; while they may work to reflect the different identities of the Asian community, it makes performative action all the easier. An organization can easily claim to be APIDA inclusive in its mission statement without actually laying out the groundwork of how they provide equal opportunities to East Asian Americans, Pacific Islander Americans, South Asian Americans, and so on and so forth. On the other hand, a student looking for a club to be a part of may jump head first into one labeled AAPI–without realizing that the club may not be catered towards the Native Hawaiian or Desi American communities, who are typically not included in the popular conception of what Asian Americans look like.

I recognize that it is fairly impossible to focus equally on every single group included under these umbrella acronyms, and in fact, I do not think it is wrong for a club or organization to target specific communities. But with the very real possibility of unequal representation, there needs to be a conscious effort to understand what is entailed and what may be expected when using certain language. The responsibility extends to the consumer of this language as well; just because a certain term signals representation and inclusion, it does not mean there isn’t further research to be done in order to fully understand how and why that language is used.

A similar tactic is being taught in terms of reading quantitative data on the Asian population in America. When data is being collected, presented, and analyzed in terms of the “Asian American” or “AAPI” population, there is the reassurance that the groups that should fall under these categories are included without the physical presence of separate numbers for these populations. For example, Southeast Asian Americans are typically shown to have higher poverty rates compared to East or South Asian Americans. However when the data is disaggregated, it is revealed that the Bangladeshi, Tongan, and Samoan populations are within the top five when it comes to the highest poverty rates in Asia America. It is apparent that even when an acronym like AAPI is used to show inclusion in data, it is important to take apart and disaggregate the numbers to better represent the reality of these communities.

The same goes for language. Even when there are no numbers attached, every use of Asian American, AAPI, APIDA, AANHPI, and other words to describe or represent real communities calls for a further examination of the meaning behind the term. While these terms are a neat, simple way to make sure everybody feels included within the language, these growing acronyms do not automatically translate to growing inclusivity unless there is actual groundwork being done to back it up.

Taking the easy route and falling into a false sense of inclusivity may be convenient. But these shortcuts continue to be exactly that–acronyms and simplified language should not take away from the quality and genuineness of what is being presented, especially when it involves real communities and the lives and identities of people.

Visual Credit: Glenn Peters

Comments are closed.