*Content Warning: subjects discussed include sexual violence, trauma with childbirth, abuse, mental health and neglect*

Growing up I was often told that I was exactly like my mother. What I didn’t realize then was that her traumatic experiences painted me in the mirror image of herself.

Thi Bui’s graphic novel, The Best We Could Do, discusses intergenerational trauma and how we come to understand our parents’ deep-rooted wounds as children of Vietnamese immigrants in America.

“Family is now something I created and not just something I was born into.”

pg.21

The story begins with Thi Bui in the hospital, as her mother (Má) awaits outside the room, unable to stomach the sight of her daughter giving birth. Amidst this, Thi Bui emphasizes to the doctor that she had no desire to be put on drugs as she felt that she would not be able to measure up to her idealized image of a mother (based upon Má) and would once again be forced to become the child (making others take care of her). The closing scene shows Thi Bui hugging her mother as she questions how she was able to do it “six times”.

The image of childbearing is prevalent throughout Má’s story, as a lot of her trauma is rooted in her first child dying of disease and her fourth being a stillbirth. Much of this is reflected in how she reacts to Thi Bui’s pregnancy, as she begins recollecting the pain of physically birthing a child and losing her children to unfortunate circumstances out of her control.

Throughout this story, Thi Bui is seen comparing her struggles with her mother’s as she feels insecurities about being a good mother like Má. Thi Bui views Má as a role model; due to her role as the sole provider, her mother acted as the foundation that held the family together. Thi Bui describes her mother as a “heroic” “Vietnamese Princess” who sacrificed everything for the sake of her children.

The relationship between Má and her daughters is surrounded by her trauma of isolation and abandonment from her childhood. Thi Bui talks about her mother’s difficulties accepting her daughters’ partners as she fears they’ll be taken away. This correlates to how Má had grown up in a neglectful household where her mother would ignore her, which led to feelings of isolation. This, along with her desire to be intellectually independent, influenced her views on marriage as a prison, but later on, she married Thi Bui’s father (Bố), due to an unexpected pregnancy. Bố would later play a role in Má’s trauma, as he would abandon her multiple times during childbirth.

Bố is often portrayed as emotionally withdrawn and paranoid. He was a stay-at-home dad who would smoke in front of his children and not care what they would do.

One of the first recollections Thi Bui has of him is hearing his frightening stories of perverted neighbors and women getting sexually assaulted by scissors. This trauma culminates in Thi Bui’s siblings hiding in closets during the night in fear of their neighbors and Thi Bui herself refraining from an episiotomy—a procedure of cutting the vaginal wall, which is sometimes done without the mother’s consent—due to the association of that procedure with the story of getting sexually violated with scissors.

Bố’s treatment of his children is a reflection of his childhood. His complicated family issues left him abandoned by his parents. He went to live with his grandparents, who would often tell him frightening stories to warn him of dangers, and around this time, he was subjected to the horrors of the Vietnam War. He had to hide for his life as French soldiers would attack his grandparents’ village, leaving countless dead bodies in their wake.

The emotional disconnect Bố had with his children is seen in his lack of care for their well-being. The influence of his relationship with his own parents abandoning him caused him to develop a much colder outlook on life. As a result, he would have difficulty expressing affection or being present for his family when they needed him most (such as when he left his wife alone during pregnancy). The stories he would tell his children to scare them were taught to him by his father (when he was present) and his grandparents. This would also coincide with Bố’s development towards paranoia as he was internally traumatized by these stories and the visceral scenes of death.

“I grew up with a terrified boy who became my father.”

pg.128

Má and Bố both have extensive backgrounds in education, having met in college in Vietnam as they were studying to become teachers. However, the Vietnam War would drastically affect their livelihood, causing them to emigrate to America in hopes of survival. In the U.S., their degrees would be deemed worthless, forcing Má to undertake any job she could while Bố took care of the children out of a desire not to work.

While coming to America, Thi Bui’s parents would often have to run and hide from the Northern Vietnamese government as they saw them as “Ngụy” (supporters of the Americans in the Vietnam War). They briefly spent time in a Malaysian refugee camp, where Má would give birth to some of her children. In America, Thi Bui’s family had difficulties assimilating both culturally and economically. Despite this, her parents still sought the willpower to continue on.

Thi Bui discusses how she had inherited a trait from her parents known as the “Refugee Reflex”, an instinct for survival. This is shown when an explosion occurs downstairs of Thi Bui’s home, and her family instinctively hides as a result of their trauma from the Vietnam War. However, Thi Bui takes the initiative to help her family flee. In this instance, the way she would inherit the “Refugee Reflex” is through her parents’ will to move forward and survive rather than succumbing to their fears accumulated from their experiences.

After Thi Bui’s son is born, he is afflicted with jaundice. While taking care of him, she remembers her mother’s story of taking care of her first child who had died of a disease early on after the birth. She compares the need to be “heroic” for her son to her mother’s sacrifices and hardships she endured. At the end of the novel, she seeks to break the cycle of intergenerational trauma through the new life she is determined to give to her son.

“That being my father’s child, I, too, was a product of war and being my mother’s child, could never measure up to her.

pg.325

The novel’s portrayal of emotional trauma is shown not only through the images but also through the spoken words of each character. This helps to engrain into the reader’s mind a story of generations. Thi Bui emphasizes the importance of understanding our family’s history as interconnected experiences we share are often a product of our parent’s struggle to survive and create a new life for us.

When reading this novel, it felt as if I was looking at a mirror image of my own family’s story. The trauma associated with complicated family dynamics, the scary stories Bố told his children and the “Refugee Reflex” that had been inherited by Thi Bui were all things I had experienced myself growing up. As children, we often forget that the reason why we develop in the ways we do is because we are the product of our parents’ story and in turn their trauma.

Just like Thi Bui, I remember the stories of my mother, who fought so hard in her life to be given a single chance to survive. When she walked out the door at 18 because she could no longer bear the controlling grip my grandmother had on her life. Even when she would sell her body to make any sort of money because she had nowhere else to go.

My father, who came to America by himself to live with his sister because nothing was left for him in Vietnam. The insecurities of abandonment he carried throughout his life due to the isolation he felt from his family back home.

The toxic environment where my parents would verbally and physically abuse one another, as a response to the resurfaced trauma held deep within. The experience of miscarriage and the toll it took on both of my parents’ mental health. That moment when my mother’s lifeless body fell to the ground as she unsuccessfully attempted to escape once more, and my father did nothing else but continue to yell.

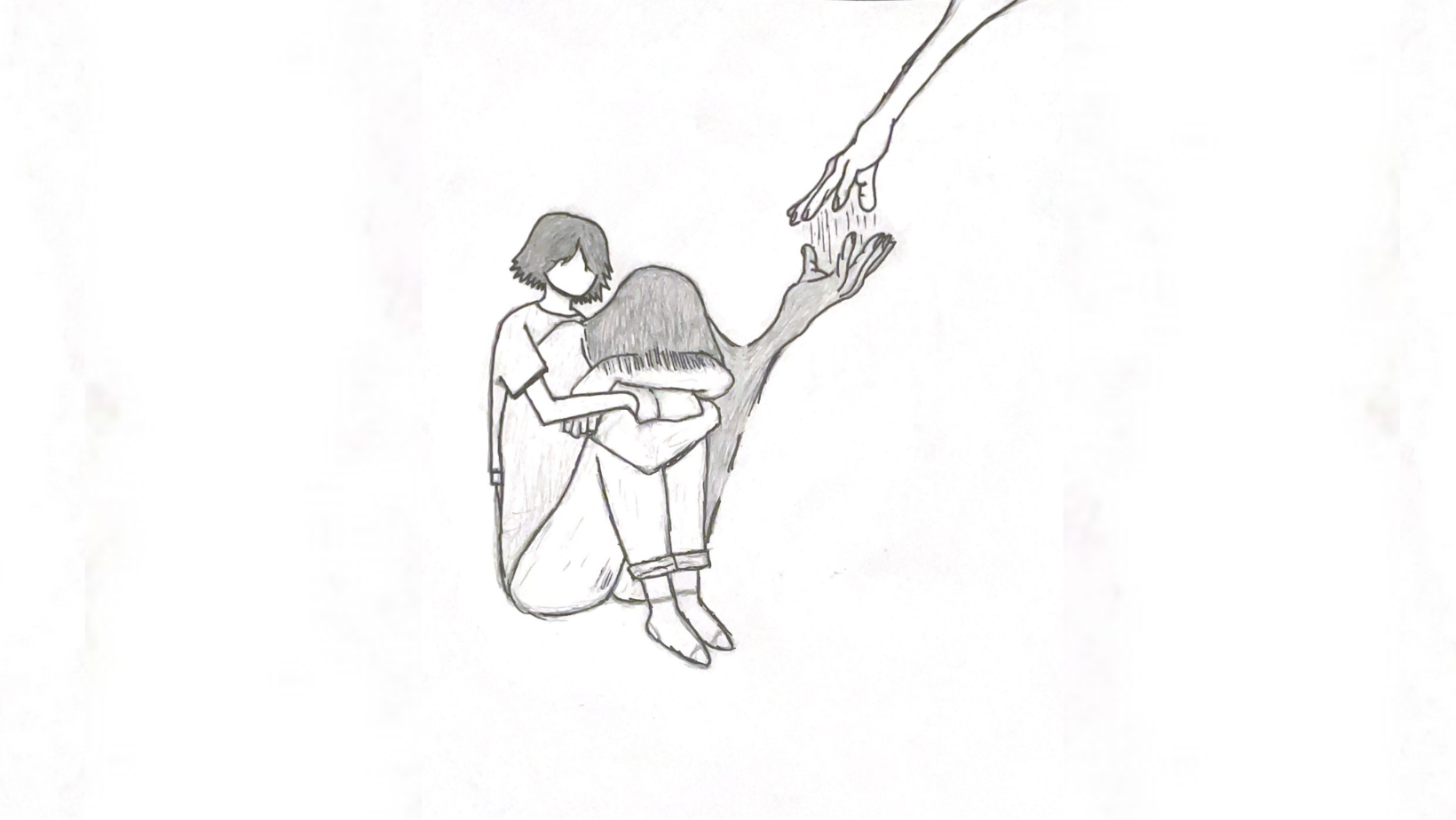

Just like my mother, I, too, tried to escape in the same way, tired of feeling alone. I, too, had walked out of my family’s life when I turned 18, and just like my father, I sought to forge a new path for myself because I felt that I had nothing left. I now sit here just like Thi Bui, seeking to stop this cycle of intergenerational trauma with the “Refugee Reflex” embedded into me through my parents’ story.

Visual Credit: Branden Barnes

Comments are closed.