BY LORA LIU AND MAY ZENG

Photos by May Zeng

Trigger Warning: This article contains the use of a racial slur as quoted in some of the exhibit pieces and brief mention of violence.

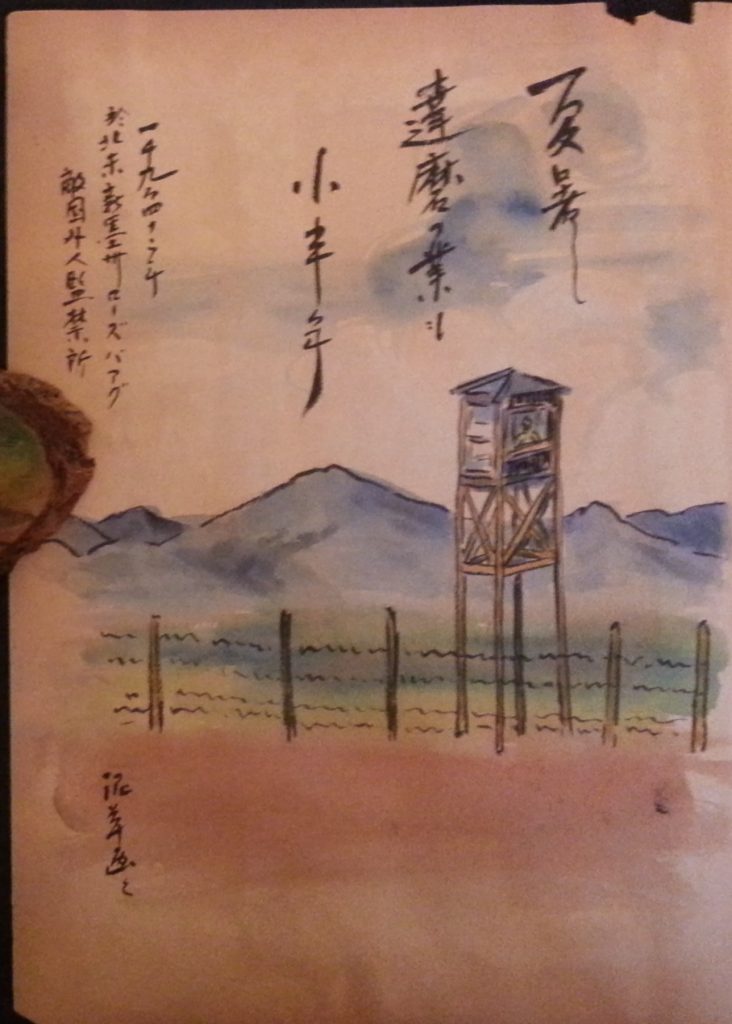

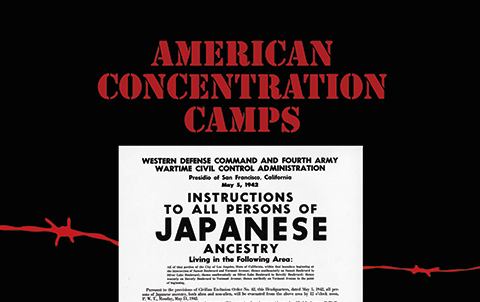

On January 18, an exhibit titled “American Concentration Camps” went up in the Powell Library Rotunda at UCLA. The exhibit consists of collections chosen from the UCLA Library Special Collections.

It is significant that the exhibit refers to the camps as “concentration camps” instead of the commonly used term “internment camps” because “internment” describes the imprisonment of foreign nationals, yet almost two-thirds of those incarcerated were natural born US citizens.

UCLA Library Special Collections states that their purpose is to preserve cultural heritage through primary sources that “tell the story of our collective past.” Rather than relegating Japanese internment to a few pages in a textbook, the “American Concentration Camps” exhibit is a display of what Japanese internment, and the attitudes and beliefs driving it, really looked like.

Q&A

Doug Johnson is a Special Collections staff member and curator of the “American Concentration Camps” exhibit at Powell Library. Including Johnson, four staff members in Library Special Collections and two scholars in the Center for Primary Research and Training put the exhibit together in just under two months.

Doug Johnson: After the election, a meeting was convened in our department to talk about what we as librarians and archivists could do to respond to the incoming administration, and a lot of ideas were floated at that meeting, and my personal idea was to have this exhibit because I knew we had tons of material on Japanese internment, and I had heard surrogates of the administration talking about that as instructed precedent for the Muslim registry and I found that very alarming and wanted to push back against that in whatever way we could.

May Zeng: What do you hope for people to get out of this exhibit?

DJ: Well, knowledge, first of all, because the tactic of the current administration to try to dismiss facts and elide history and twist historical record to their own end and I think we have to assert the truth about what really happened. And I hope with that knowledge, will come compassion and energy and a desire to both resist any injustices that may be visited on vulnerable populations.

MZ: Have you worked much with this subject matter before?

DJ: No, I haven’t. I’m Japanese American, and I hadn’t heard about this at all until I was a kid during the Reagan years when the redress movement was going on; that was the first I heard of it. My family was never affected by this because my mother was from Japan, but it was startling to me to learn about that in the 80s. And though I had some passing familiarity with it over the years, I never really studied the topic until taking on this project.

MZ: What did you learn from working on this exhibit?

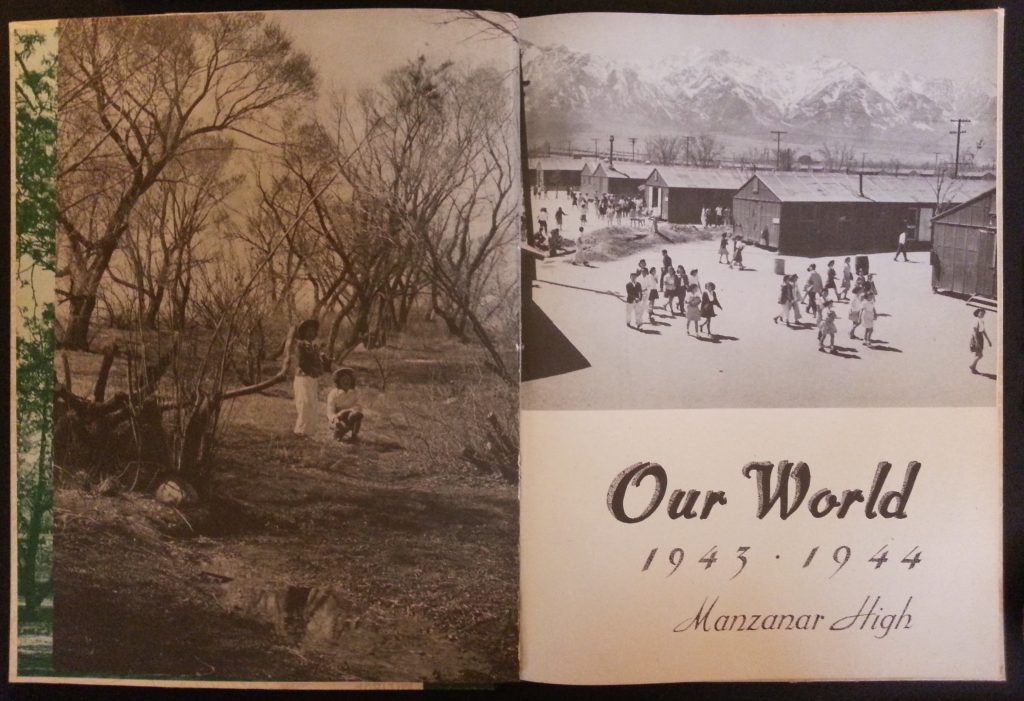

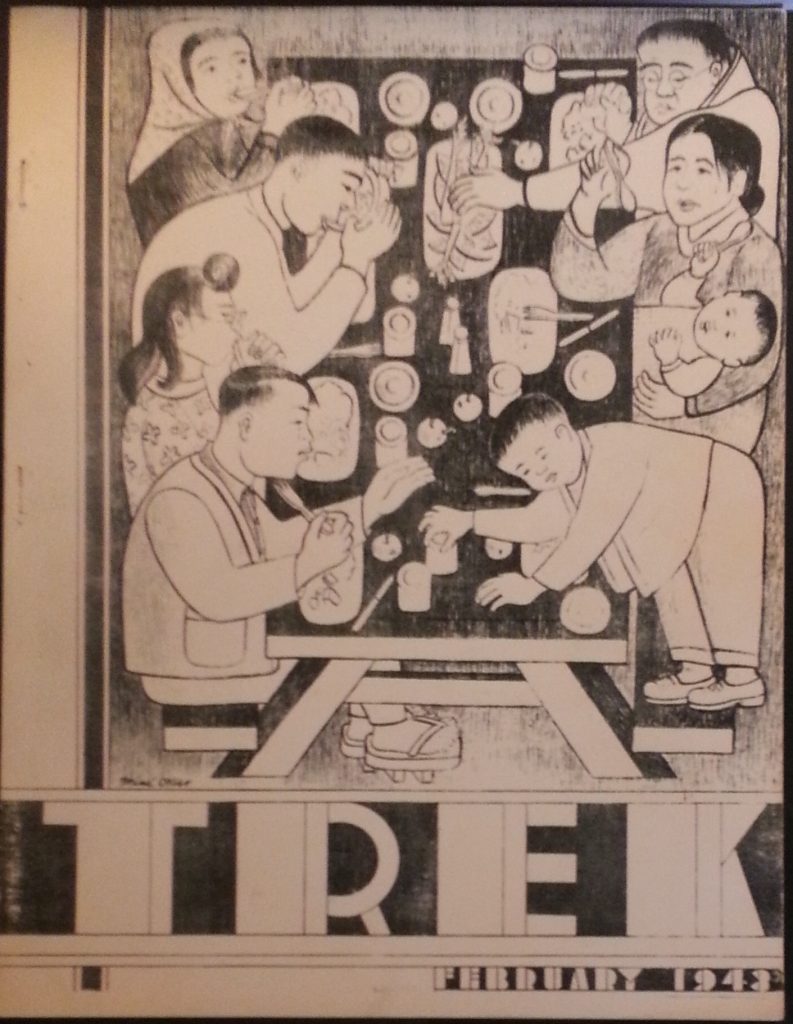

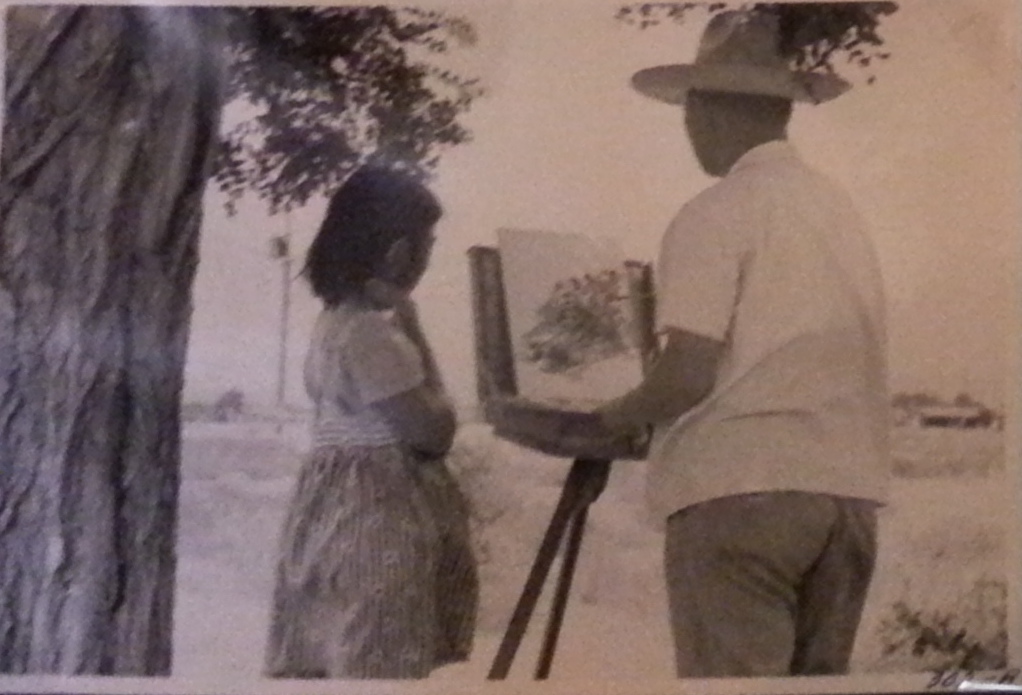

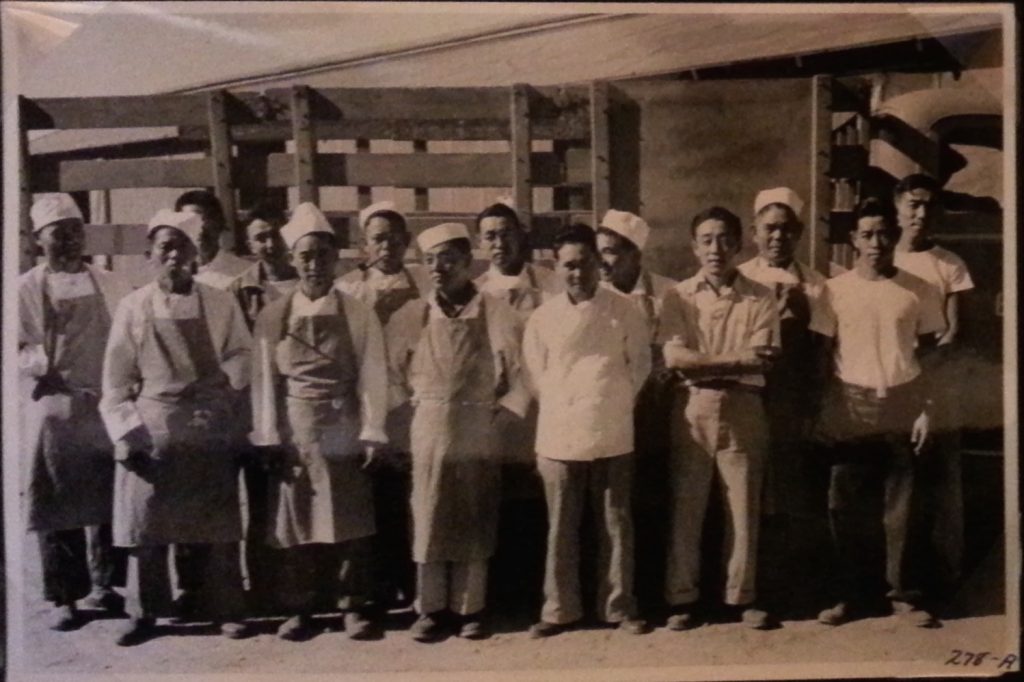

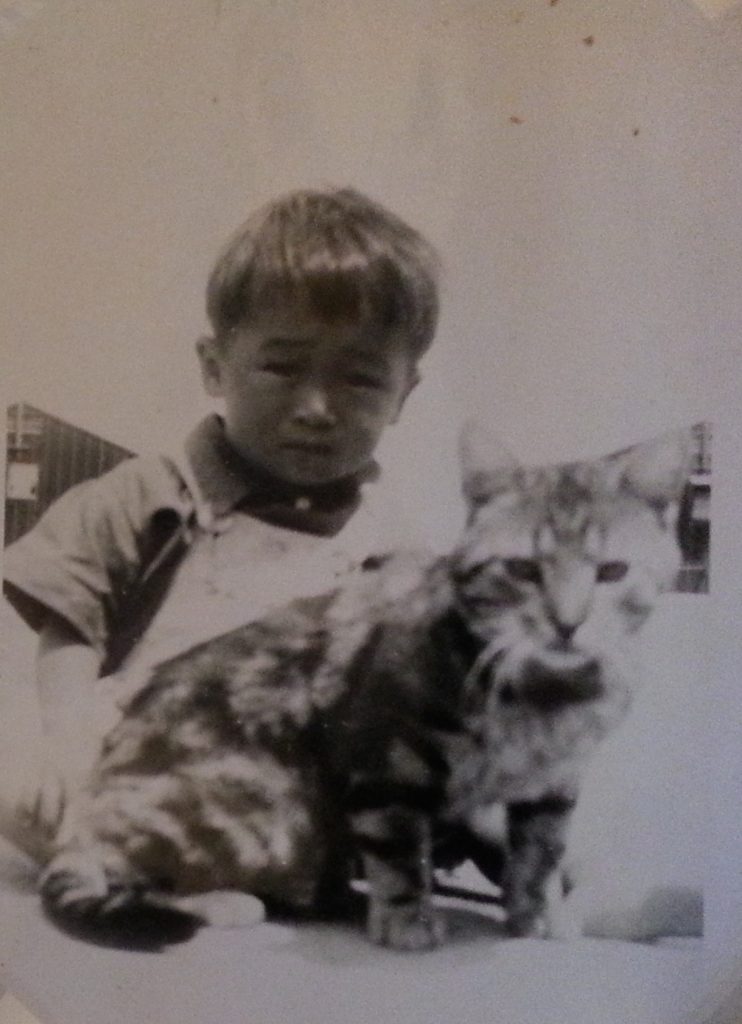

DJ: I’ve learned that people are really resilient. And when I started this project, I had the idea that I didn’t want pictures of people smiling because at the time, there was a lot of propaganda by the US government to take pictures of people smiling in the camps, and talk about how nice their homes were and how good the food was and all that kind of stuff. I did not want to do that. I kinda wanted it to show it as a really oppressive, horrible place to live, which it was. I truly believe it was, but I also realized that by not including some of the positive aspects of camp life, I was doing a disservice to the people who lived there because they were incarcerated for an indefinite period of time and they had to live, they had to find some way to live in that condition, some way to make themselves happy, and go to school, and fall in love and play sports and sing songs and do art. So we included one of the cases revealing that aspect of camp life. [It’s] my favorite case now, even though it’s the case I initially didn’t really want to have.

We all learned a lot. The interesting thing about working with primary materials like this, you see the small little details, but you don’t really get a sense of the big picture of things…It’s different from your normal historians’ view, which tries to give you a big picture. It’s a little more hands on and personal, and maybe myopic in some ways, but still very rich.

MZ: Do you think that might be a problem, for a lack of a better word, for someone who doesn’t know anything and walks in and doesn’t get the big picture?

DJ: Yeah, I do think that could be a problem. There aren’t a lot of dates and names and numbers, and the things that are commonly associated with a history class. You get these little snapshots and slices of life, but I hope they’re compelling, and if you want to learn the whole story, there are ample resources in our libraries to learn about it. So if your imagination is seized by one particular item or artifact in the exhibit, that could lead you on to discover the greater context, the greater story of the whole episode.

Gallery

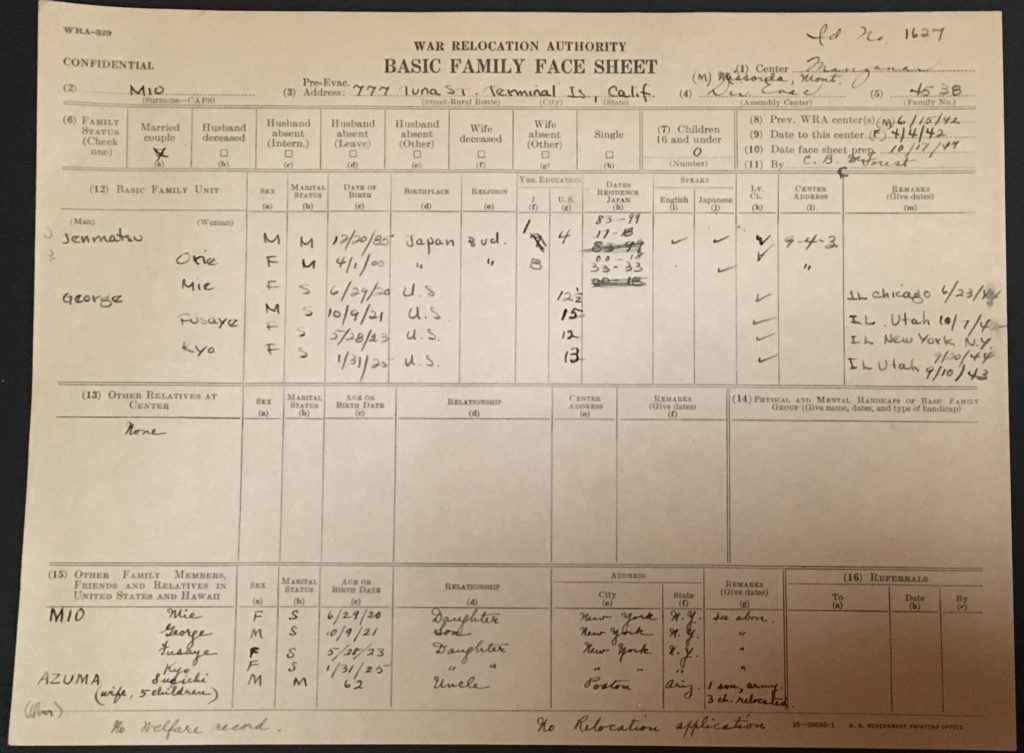

In one of the displayed documents, labeled “Basic Family Face Sheet,” basic information of six members of a Japanese American family’ was listed, including their countries of birth. Of the six, only one had been born in Japan, yet due to their ancestry the whole family was put in a camp.

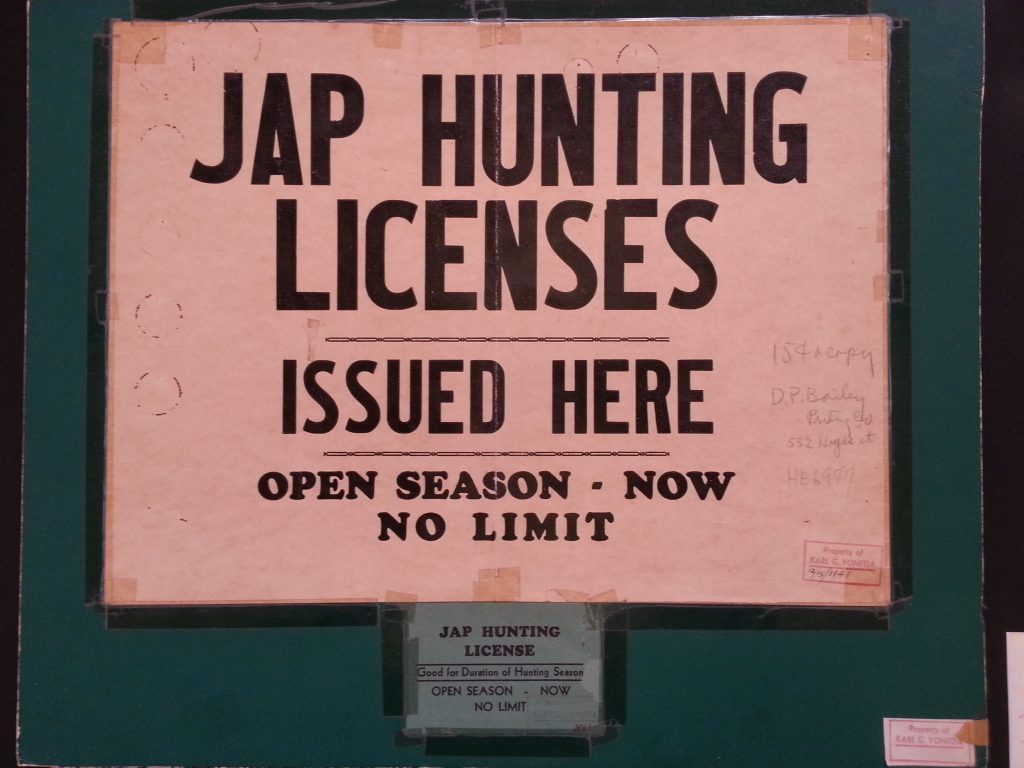

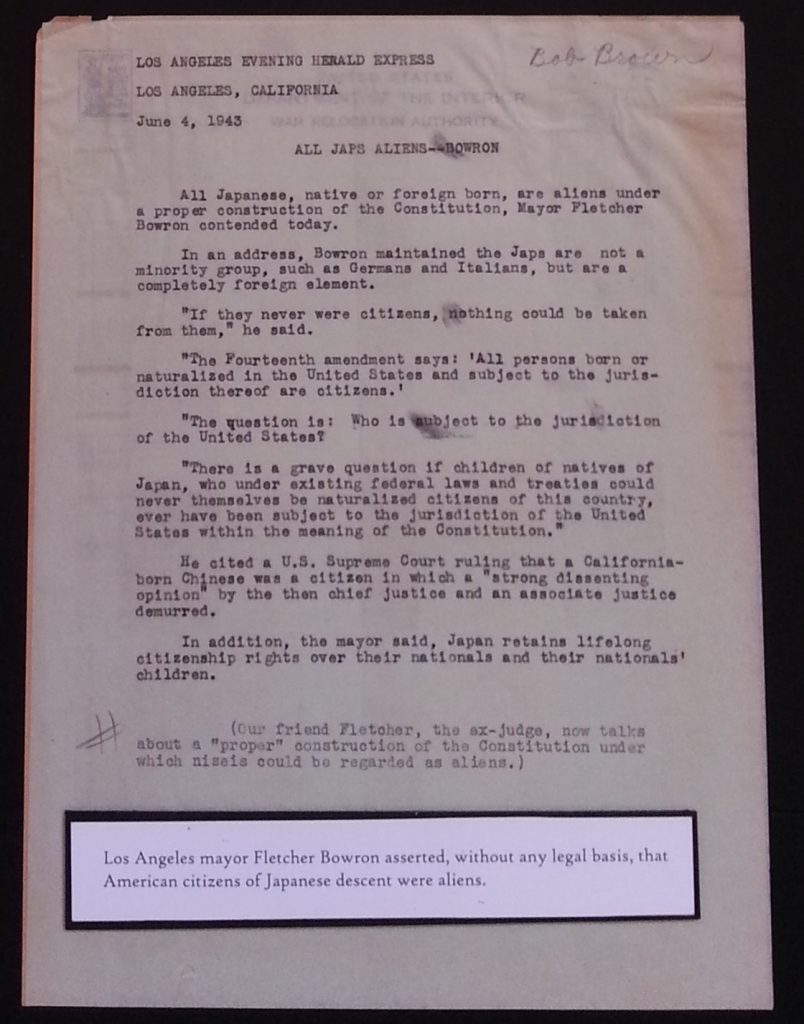

The Los Angeles Evening Herald Express shared LA mayor Fletcher Bowron’s belief that “All Japanese, native or foreign born, are aliens under a proper construction of the Constitution.” According to Bowron, “the Japs are not a minority group, such as Germans and Italians, but are a completely foreign element.” Behind Executive Order 9066 was the idea that, “if they [the Japanese] never were citizens, nothing could be taken from them.” By denying Japanese Americans their citizenship and “othering” them as foreign aliens, Bowron and others who shared his beliefs were able to justify stripping them of their businesses, their homes, their land, and their basic human rights.

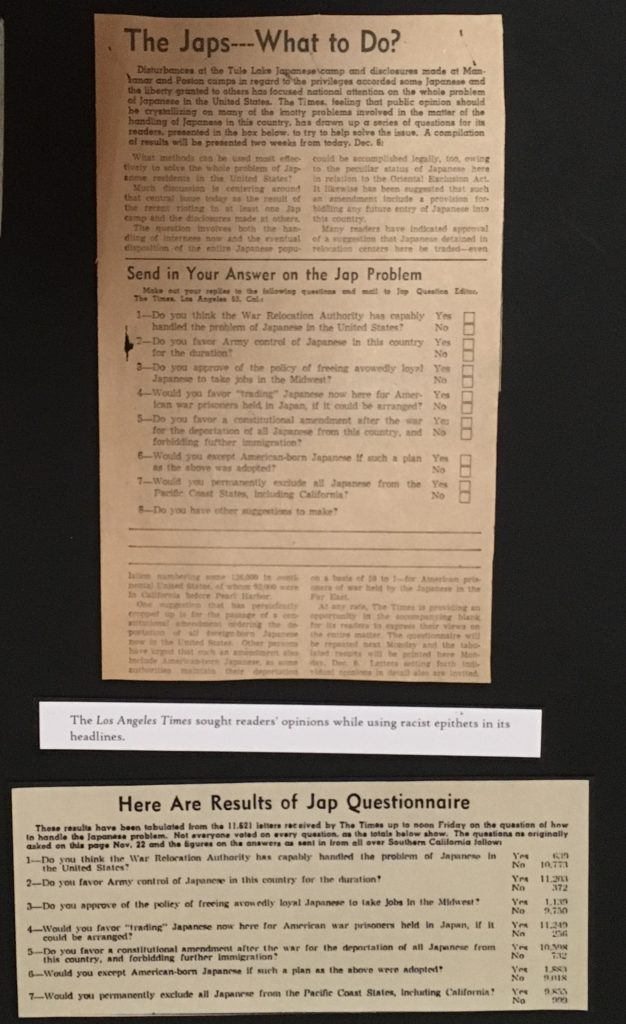

The Los Angeles Times’s “Jap Questionnaire” featured in the display reveals that when asked, “Would you permanently exclude all Japanese from the Pacific Coast States, including California?,” 9,833 Southern Californians answered yes while only 999 answered no.

For another question, “Do you favor a constitutional amendment after the war for the deportation of all Japanese from this country, and forbidding further immigration?,” 10,598 answered yes while 732 answered no. It was not enough that the Japanese were stripped of their land and were forced into concentration camps where they had to complete loyalty oaths. Many still wanted them physically removed from the country.

Japanese Americans were not safe either. The follow-up question, “Would you [accept] American-born Japanese if such a plan as the above were adopted?” saw 1,883 say yes while the answer was still no for 9,018.

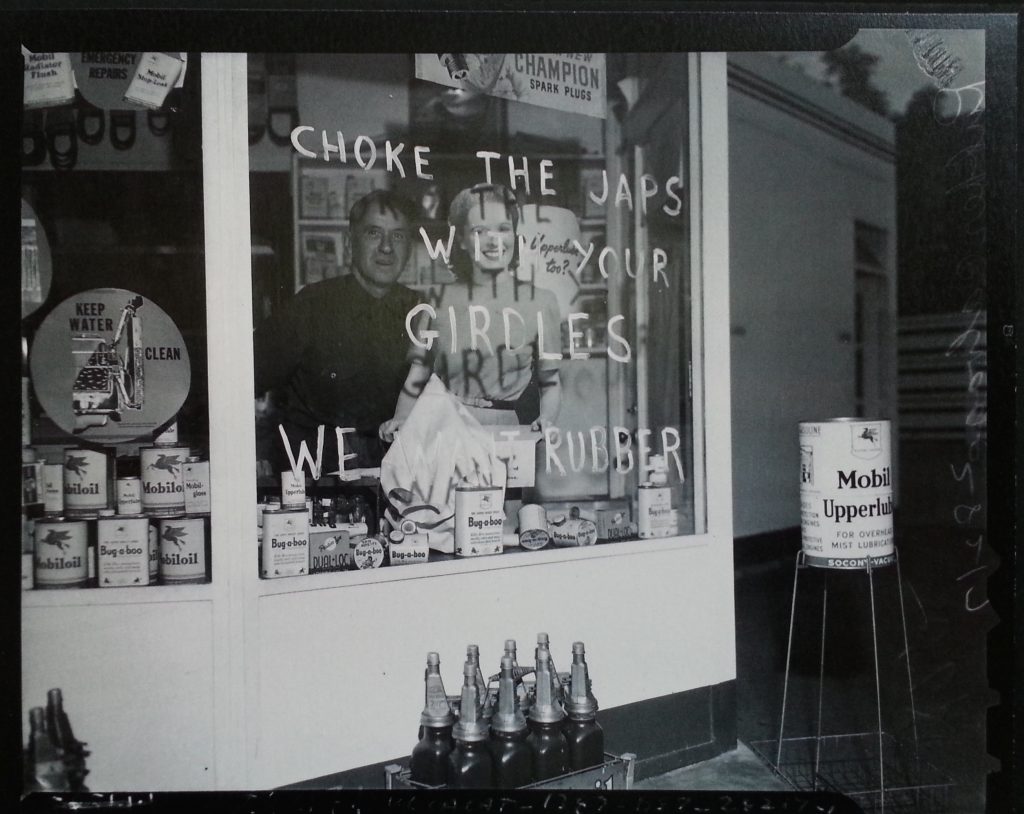

A white man and woman smile behind a glass storefront. Written on the glass in all caps, “Choke the Japs with your girdles. We want rubber.”

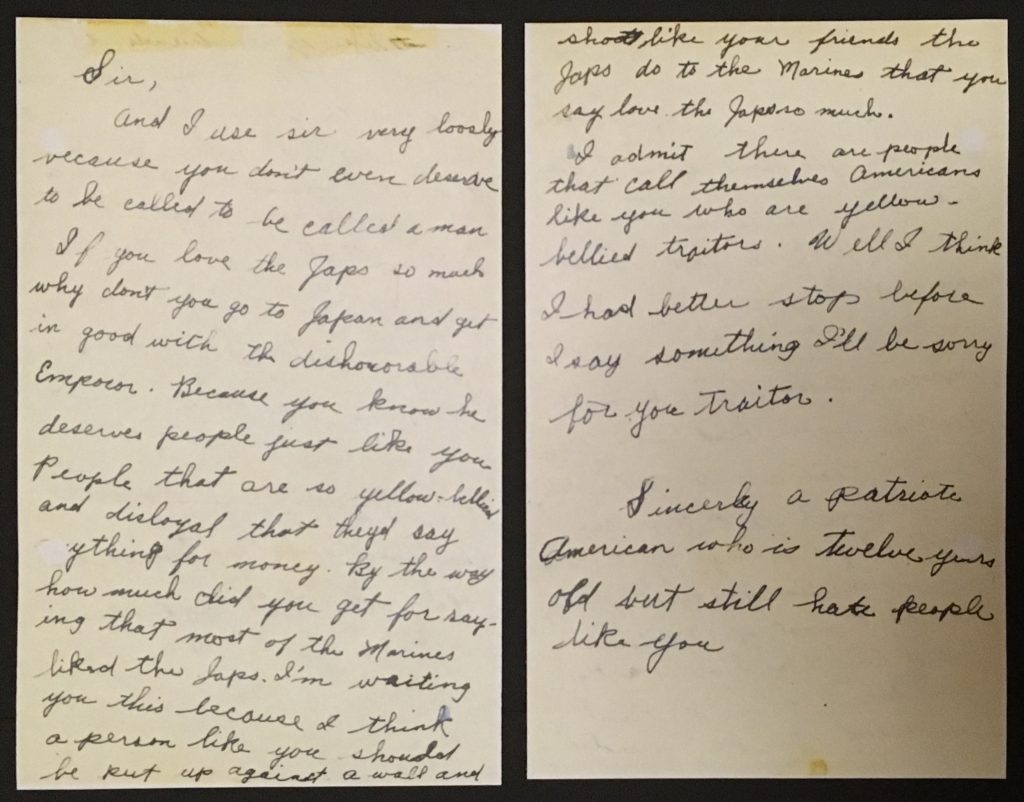

From caption card: “Ralph Lawrence Carr was the governor of Colorado. A conservative Republican, he advocated that the Japanese in America be treated with respect and compassion. This letter, written by a child, reveals the political backlash Carr faced. He left office in 1943.”

The letter reads:

“Sir,

And I use sir very loosly [sic] because you don’t even deserve to be called to be called [sic] a man.

If you love the Japs so much why don’t you go to Japan and get in good with the dishonorable Emporor [sic]. Because you know he deserves people just like you. People that are yellow-bellied and disloyal that theyd [sic] say anything for money. By the way how much did you get for saying that most of the Marines liked the Japs. I’m writing you this because I think a person like you should be put up against a wall and shot, like your friends the Japs do to the Marines that you say love the Japs so much.

I admit there are people that call themselves Americans like you who are yellow-bellied traitors. Well I think I had better stop before I say something I’ll be sorry for, you traitor.

Sincerely, a patriotc [sic] American who is twelve years old but still hate people like you”

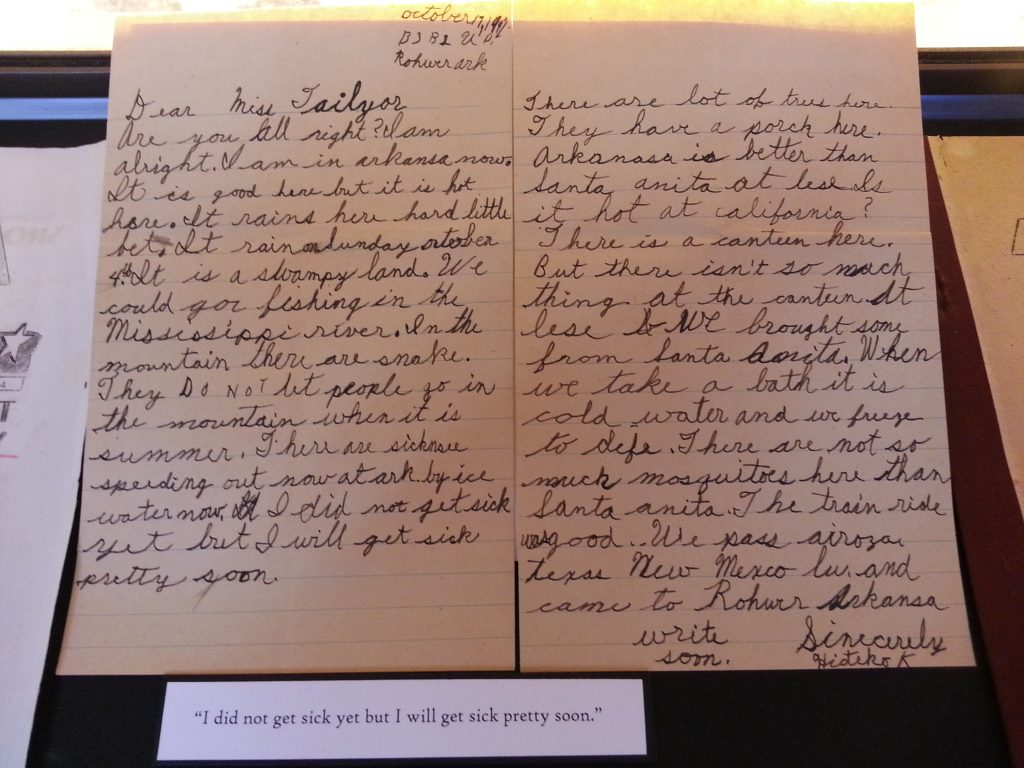

Letter from a young girl (age unknown) interned in Arkansas writing back to her teacher in California.A young girl tries to keep a brave face and be optimistic despite how bad things are at the camp as she writes to her teacher back home. The letter reads:

“Dear Miss Tailyor

Are you all right? I am alright. I am in arkansa [sic] now. It is good here but it is hot here. It rains here hard little bet [sic]. It rain on Sunday October 4th. It is a swampy land. We could go fishing in the Mississippi river. In the mountain there are snake. They DO NOT let people go in the mountain when it is summer. There are [sicknesses spreading] out now at ark. by ice water now. I did not get sick yet but I will get sick pretty soon.

There are lot of trees here. They have a porch here. [Arkansas] is better than Santa Anita [Racetrack] at lese [sic]. Is it hot at California? There is a canteen here. But there isn’t so much thing at the canteen. At lese [sic] we brought some from Santa Anita. When we take a bath it is cold water and we freeze to defe [sic]. There are not so much mosquitoes here than Santa Anita. The train ride was good. We pass [Arizona], Texas, New Mexico, and came to Rohwer Arkansa [sic].

Write soon.

Sinecerely [sic]

Hiteko K”

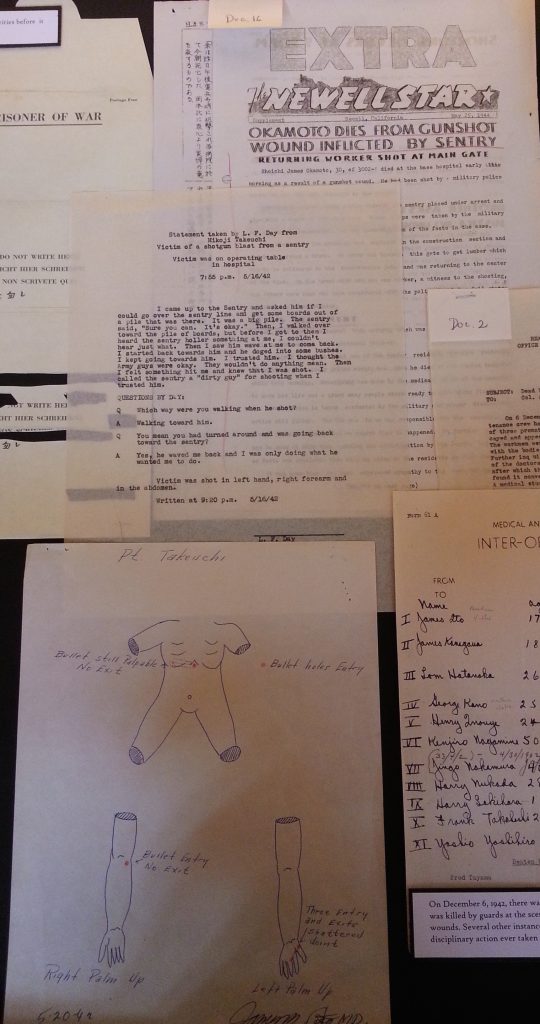

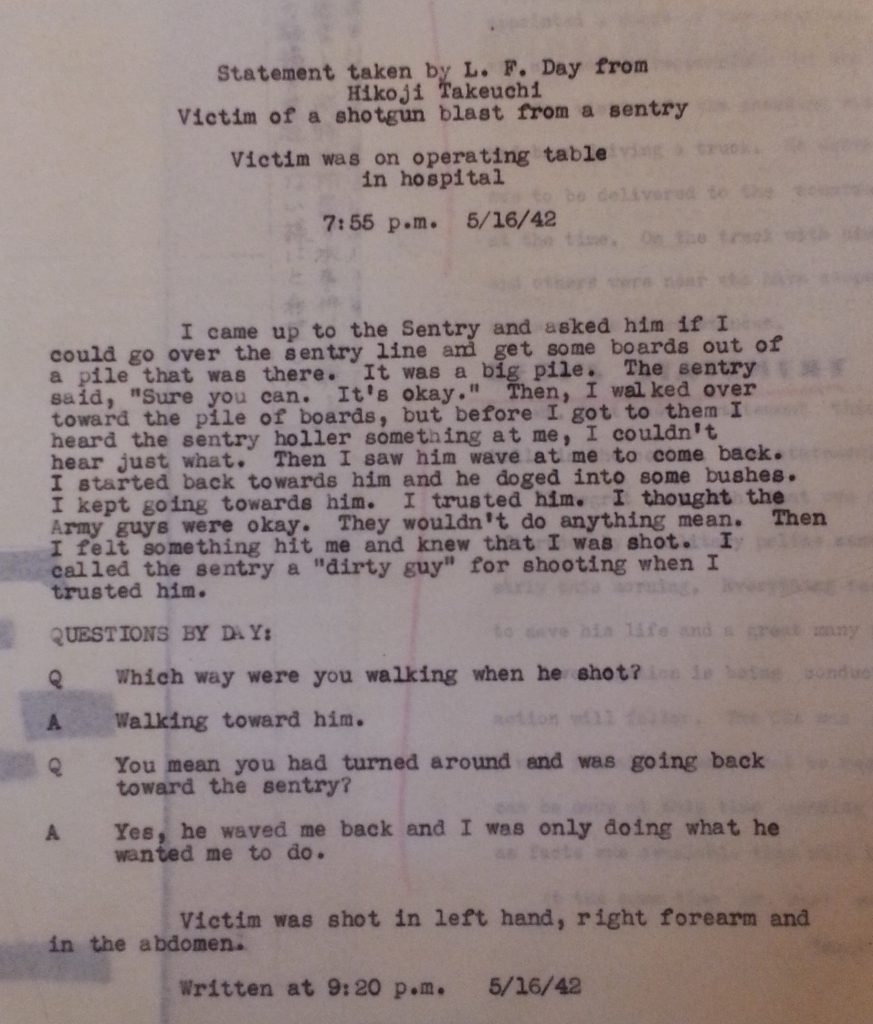

Johnson found many examples of people being shot by guards and sometimes killed as a result of those gunshots. For example, Okamoto was “gathering wood just outside the gates and a guard shot him. There are multiple eyewitness accounts confirming that. If you follow the story, you find that the guard never suffered any kind of disciplinary action, much less criminal prosecution for what he did.”

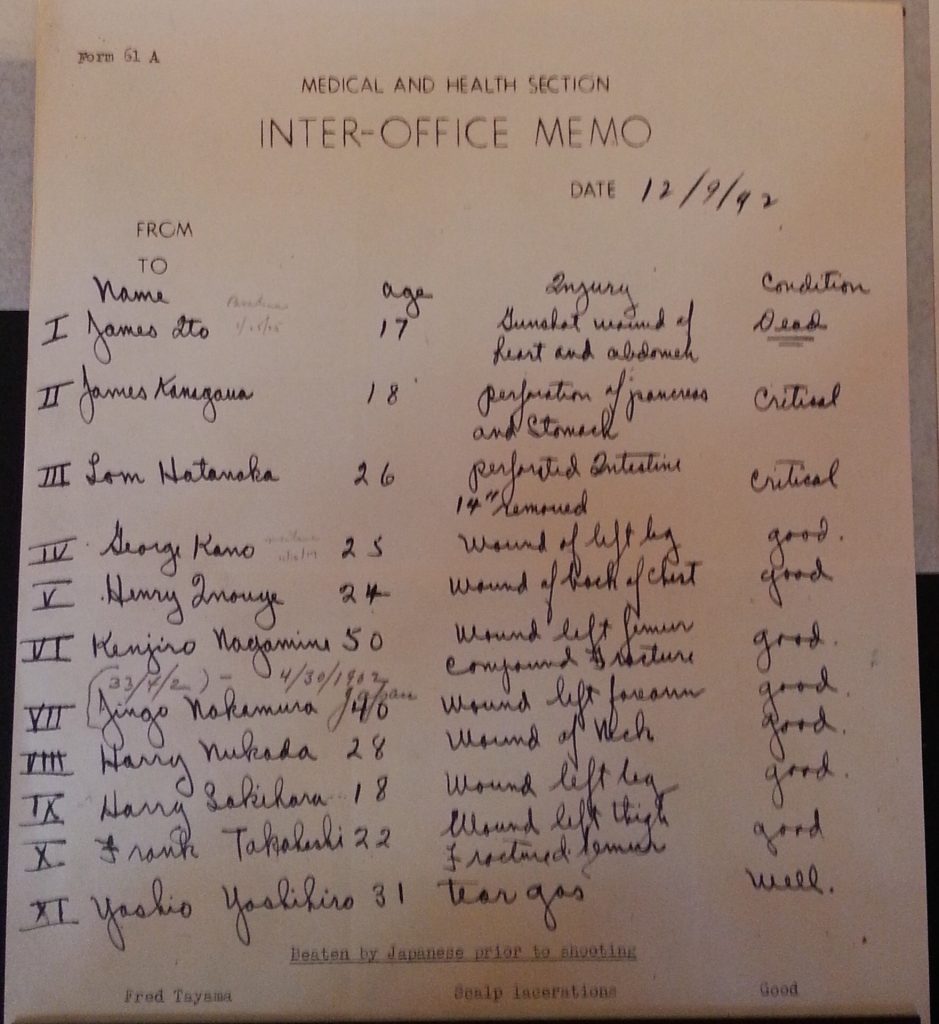

Similarly, two teenagers, 17 and 18 years old, were killed at a riot at Manzanar around the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor. No guard or soldier faced any disciplinary action for the killings.

—

This year marks the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, but it is clear that the same type of justification behind Japanese internment is present almost a century later.

The “American Concentration Camps” Exhibit is on display in the Powell Rotunda until March 24.

Comments are closed.