Contributing authors: Cindy Tran and Katrina Galian

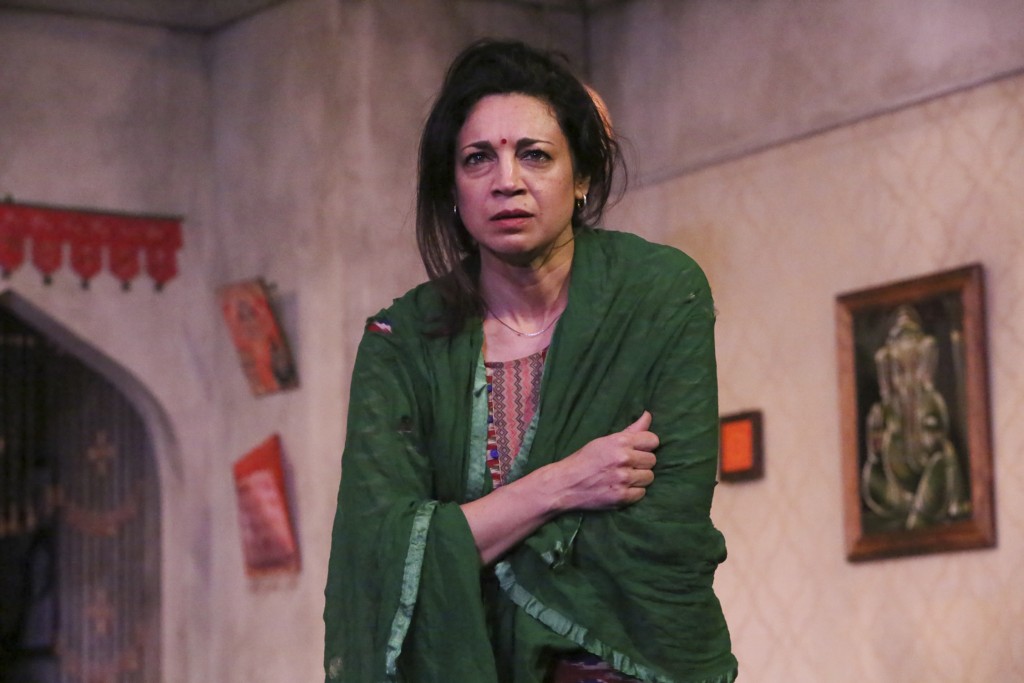

“Free Outgoing” by Anupama Chandrasekhar opened at East West Players in Little Tokyo on Wednesday night to an almost sold-out audience. The theater company’s 51st season, Radiant, focuses on featuring stories by and about women. “Free Outgoing” is an intricate play centering around traditional values in conservative Chennai, India.

When teenage schoolgirl Deepa is caught on video with a boy in a classroom, her entire family’s reputation is thrown into disarray. With the aid of mobile technology and social media, the video goes viral all over India. Malini, Deepa’s mother, must cope with each new consequent development as it comes to light, while also trying to protect her daughter from both the sexual double-standards and the prying eyes of society.

“Free Outgoing” is directed by Snehal Desai, who is currently in his first year as Artistic Director of East West Players. He is the first South Asian Artistic Director at East West Players. Prior to the Los Angeles production, “Free Outgoing” played at Boom Arts in Portland, Oregon in March 2016 with the same director and four of the same actors.

Chennai-based playwright Anupama Chandrasekhar is currently the first international artist-in-residence at the National Theatre in London. We were very fortunate to speak with her last week at the David Henry Hwang Theater in Little Tokyo as she spent preview weekend working with the East West Players cast and crew.

May Zeng: Deepa and Jeevan, the two in the video, are never shown in the play. Can you tell us about your choice to omit those characters?

Anupama Chandrasekhar: The primary reason why I omitted Deepa from the play is that I wanted to focus on the repercussions on the society by this act of sexual indiscretion by a teenage girl. [It’s] not so much on if you’re throwing the pebble into the water, but the ripples the pebble created. The best way I felt that I could do that was not to have the girl on stage because if I did have the girl onstage than the question would be, “was she right or was she wrong?” That was not my intention to question this girl’s morality. It was for me a way to look into society and the double standards of society.

MZ: You were living in India when the Delhi Public School MMS Scandal happened in 2004. What was that like?

AC: It was the beginnings of the mobile revolution. It was also the beginnings of the media revolution. Television was just starting to take off in a huge way and the kind of coverage that the family was getting it just exploded something small into something that captivated an entire country. I was watching in horror what was unfolding day after day, minute after minute, and the poor girl was vilified all across the news channels. For me, what was disturbing was how the boy was going scot-free and the girl was being vilified. That was what prompted me to start the play.

MZ: What kind of parallels were there of the things being said about the girl in the DPS MMS Scandal in comparison to the things that were being said about Deepa?

AC: I’ve used a lot of my own imagination [in creating the reactions in “Free Outgoing”]. A few months after the MMS incident, a Tamil actress wrote in her column that women should practice safe sex [to prevent HIV/AIDS], and again, that just exploded way out of proportion. The general public thought she was promoting premarital sex. With both these incidents, the aspects of female sexuality were clearly disturbing the Indian community. So the question regarding female sexual rights was something on my mind when I was writing it. I mean, do girls have right to their bodies at all? Do girls have sex? That was something that was playing all in my mind when I was writing this play.

Cindy Tran: How did the reactions to the play differ in the different countries that the play was performed?

AC: Different countries, different reactions. Sometimes same reactions too. I did not expect the kind of positive responses from the western world because I always thought, “Why would the West be interested in an Indian play?” and what I’ve discovered is that the motivation of parents are the same across the world. They want their children to be better than they are. They want their children to succeed. They want to protect their children. I’ve found that perhaps the Western world is not as different than the developing world that I had imagined; that people in the Western world too have a concern about the role of technology and teenagers’ sexuality and sexual lives. It’s a concern that is still being explored and discussed even now when you’re talking about cyberbullying and about sexting.

What was also sad was a few months before the play opened in Canada in 2014, there were two separate incidents of young teenage school girls who were [cyber-bullied and committed suicide], So cyberbullying was very much in the full front of public consciousness when the play opened in Canada. There was an added layer of relevance when the play opened. So [the reaction was] extremely positive, extremely touching responses from the audience.

MZ: How do you think the climate in Chennai has changed since 2007, when the play was written? Is it still a very conservative city?

AC: I think it has become more conservative in the last ten years. And often there is a question of “what constitutes Indian culture or Tamil culture?” and the way a good Indian girl should behave. And I find those discussions regressive and very Victorian in the way they think – society thinks – the way women should behave. Whereas technology is ensuring that people progress in a certain direction, you have a very conservative society trying to go in the opposite directions. It is a play about the conflict between the old and the new. between technology and the conservative society.

MZ: Can you tell us a little bit about your transition from journalism to playwriting? Does your journalism background influence your playwriting?

AC: When I was a journalist, I didn’t think of playwriting as a career – it was not part of my agenda at all. I just kind of accidentally got into playwriting. I studied journalism at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC). There was one particular program that I was absolutely fascinated with and that was long-form journalism. The art of literary journalism is similar to the art of creative storytelling, except it is completely dealing with facts. [Literary journalism taught by Professor Walt Harrington] was one of the most inspiring classes that I’ve been in. I’ve often found that in researching my stories for my plays, I am using techniques that I have learned in that class. How do you ask questions? How do you get the details? That sort of thing.

Television news here and in India are not that dissimilar in that a fact is often exaggerated in order to get television ratings. So you find a space that has been left vacant by this new journalism, the television journalist. I find that some questions aren’t being asked, and I think the role of playwright now is to ask those questions. We [playwrights] are not hampered by facts, but at the same time we can get to the truth of the matter by looking at the gray areas, by looking at how people behave in certain circumstances. I think our job and the jobs of journalists are very much similar. and somehow now I am finding that a lot more playwrights are occupying the same space that journalists once had.

MZ: Why is water constantly mentioned in the play?

AC: I come from Chennai, the southeast coast of India, and we have a perennial water problem. The year I started writing “Free Outgoing,” we had the most severe drought. We really had to literally run down from our flats with buckets in our hands when the water comes to our street. The water was being rationed by the government, and we would hear the lorry (truck) water tank in the beginning of the road because he would honk, and we all rushed down stairs with our buckets. Because our flats didn’t have lifts, we had to take as many buckets of water as possible because this was the water we used for cooking and washing purposes. Because we lived on the coast, our wells have been corrupted by salt water so potable drinking water that particular year was very difficult to find. As I was writing, you start to look at the type of pressure a family can face and the first question I had to ask myself was “What happens if there is a lot of crowd in an apartment complex?” and “How does that affect a community?” At that point [the water crisis] would have been the primary problem that we [were] facing. Water becomes a metaphor for time. Time is literally running out for this family – so is the water – because of the act of indiscretion by the child – this 15-year-old teenage girl. It’s a family in crisis, in tremendous crisis.

CT: What does the title of the play, Free Outgoing,” mean?

AC: In 2007, mobile phones had just started to catch on, so companies were offering free outgoing calls to families. But it’s also, in a way, about Deepa. She was free, she was outgoing, but obviously she becomes less free and outgoing by the end of the play.

I would say that in a conservative society, often it is the free, outgoing girls who are brought down. And I’ve noticed that somehow a good girl is a girl who is silent, or who is quiet, or who does not cross the bounds of society.

MZ: What is the importance of Tamil culture in this play?

AC: I mention the bounds of society and those are bounds that are etched really deeply in Tamil society. We are far more conservative than say, Bombay or New Delhi. You are looking are a very conservative society, a very traditional society, a culture that is proud of its [classical] art forms, its conservative nature, but then you have to watch the full play to understand how that particular society functions.

MZ: What would you want young adults, such as college students, to get out of in this play?

AC: I wrote this play about Tamil society but it could well be about the society you come from. Be aware of the sexism and misogyny in your society. Sometimes you are so used to it that you take it for granted, that it is how our society is. But it shouldn’t be, and there has to be a change. So I hope that by watching this play, youngsters would be aware of the sexism that a lot of girls are facing across the world, and also be aware of how our technology can take control of a person’s life.

Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

If you are interested in learning more, check out the “Free Outgoing” study guide compiled by Nightwood Theater, where the play was premiered in North America.

“Free Outgoing” 90 minutes

East West Players, directed by Snehal Desai

Runs February 15 to March 12, previews February 9-12

David Henry Hwang Theater in the Union Center for the Arts

Single tickets $35 – $50

Pay-What-You-Can night Thursday, February 16, 2017 at 8PM

$5 discount for students with valid ID and senior citizens, $10 off for UCLA Asian Pacific Alumni members

Comments are closed.