My mother propagates plants next to the kitchen sink, slipping cuttings into plastic bottles, laying seeds down in shallow dishes.

They soak, stagnant, in their isolated pools of water.

In between cycles of dishwashing, my mother watches them. She waters them. She sets them towards the sun, these things she has cut and brought here herself, and she waits for them to grow.

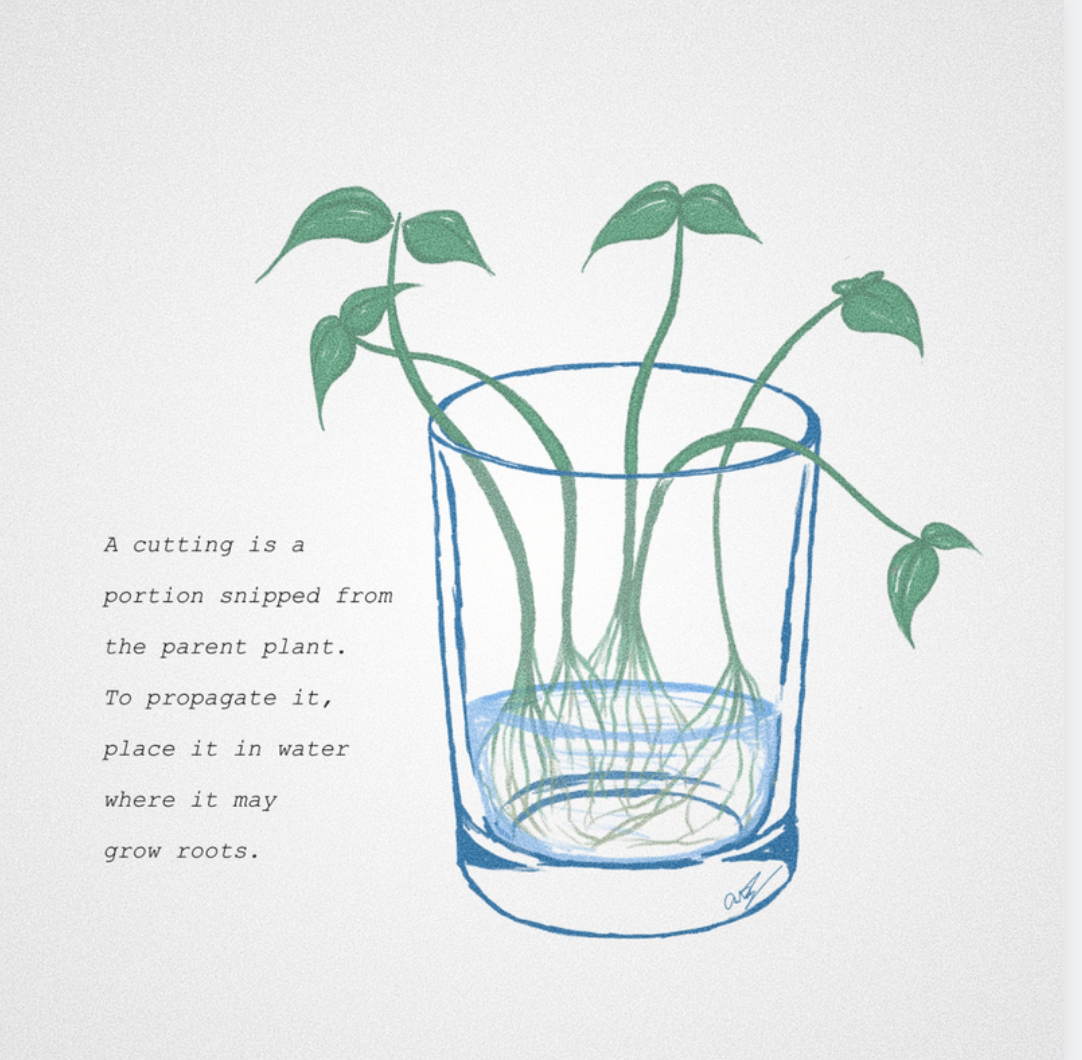

A cutting is a portion snipped from the parent plant. To propagate it, place it in water where it may grow roots.

My mother’s last name is Yang and her family tree grows 6,773 miles away in the humidity of Taipei, Taiwan. I am part of the lone branch of this family tree that has made the trip overseas and settled permanently in foreign soil. I have never known how it is like to be raised where our roots run deep.

There is a separation between the branch that grew with the tree and the branch that did not. I was set without roots into American water, planted in the foreign soil of a suburb filled with English-speaking households and Hilton hotels. To reach for the body of this tree and its ancient roots would mean reaching back over 6,773 miles, a 16-hour time difference, and a language barrier.

Cuttings do not strive to reattach to their family trees. They do not remember the trunk from which they were cut, the soil that had once nurtured their ancestors.

Cuttings sit in their isolation, and they wait.

Plants without water cannot grow.

My mother submerged her children in a world of red bean soup and conversations in Mandarin. Our family friends were like us: individual family units from a tree back in Taiwan, speaking a language that does not come easily to their tongue.

We ate mooncakes on Lunar New Year and watched videos of the Taipei skyline lighting up with fireworks. I sat in the back of the car on long rides, the crackle of the Chinese radio station lulling me to sleep with ads for medicine and insurance and language lessons. On our trip to Taiwan, I tried to blend in with the children and keep up with their games.

When they laughed at the way I spoke, I stopped speaking.

Plants without roots cannot stand.

There is a strange solidarity between children who are no longer fluent in a language they once knew well. The networks we build of our own volition determine how we identify ourselves and how firmly we are planted.

I built my networks in American soil.

This is the land of baseball games and reaching for fly balls that I will never catch. This is the land of hot dogs and hamburgers and apple pie. This is the land of my father but not his forefathers. This land, my land, your land—a child’s song of communal ownership, of one blanket identity. A song with words I could pronounce.

I was repotted from the isolation of my mother’s plastic cups, her shallow dishes, the little counter space by the kitchen sink. I drew up from the soil.

I built my identity off what I could find.

Plants grow towards the sun.

The cuttings next to our kitchen sink sit in front of the window and must choose to grow between two directions: towards my mother and the water she provides, or towards the backyard and the promise of sunlight from beyond the glass.

I chose to grow towards the sun.

It is hard to turn from the window when it is so bright outside, when the messages I hear are taught in classrooms and passed onto me by friends. We all tend to go towards the light, away from whence we came. We all tend to reach for things that shine the brightest.

When I turn back to my mother, I look across a distance that grants clarity—I see how the differences between us have multiplied. I am a branch of a branch carried overseas half a lifetime ago. I am a cutting of a cutting that once knew a tree.

I am not like my mother.

Her roots are not my roots. Her tree is far away, and the sun she grew up with is different than the one I know. I have had to grow my own roots in this ground and come to terms with the new combinations of water and soil, air and sun. There is more to me than my role as a leaf on a family tree that I wish I knew better, a family that I hold close to my heart but is too far to touch.

Perhaps we are not just a family tree but a collection of branches tied together by blood—a tree reaching beyond the bounds of a single plot. Handfuls of cuttings in our new planters, setting down roots as we are propagated into new life and individuality. Separate parts of the same whole with the freedom to grow where we will.

We grow of the same blood but stand with our own roots. We bend where the sun is strongest.

So I will claim this face that looks like it can speak Chinese as I claim my tongue that cannot. I claim my heritage as much as I claim my right to vote here. Perhaps I am not like my mother, but she still claims me as her child.

Perhaps I am not like the tree, but it still claims me as its own.

My mother propagates plants next to the kitchen sink, watching cuttings develop root systems in plastic bottles, observing seeds sprouting leaves in shallow dishes.

They sit, patient, in their little mounds of soil.

No matter how they grow and twist away from her, my mother still watches them. She still waters them. She still sets them towards the sun, these plants she has nurtured and loved, and she takes pride in their growth.

Comments are closed.