The life cycle of a single plate of food is fairly short. Conceived of ingredients brought together from a grocery store, a dish lives a quick life in the time it takes to migrate from kitchen to table, only to disappear quietly in the shuffle of forks and chopsticks. A lifespan contained within a matter of moments, sometimes prolonged by a trip to the fridge. Considering the duration of the average dish’s lifespan, it takes a lot of care to preserve them in memory past the time of their passing, to ensure that they are not swallowed and then forgotten.

A certain few have demonstrated a remarkable ability to survive over the years, their recipes passing from mind to mind, creating countless reproductions of the same product across households and generations. It’s these that we remember, and these that we hold close. They are the stuff of childhood memories, sunk deep enough in traditions that they have grown roots threaded through culture, trailing the boughs of family trees. They hold enough weight to last, enough importance to be remembered — they are part of enough collective memories that they cannot be erased even when forgotten by the individual. And it is this weight, this importance, that lets them reproduce — through stories, through traditions, through a strange sense of ancestral nostalgia that comes from eating what others had created and eaten and loved enough to leave behind.

My favorite part of Chinese food is the meanings. Dumplings in the shape of gold nuggets for wealth. Noodles long enough that they symbolize a life unbroken, longevity held within their coils. Another tangyuan eaten, another year lived; a fish left half-finished on the table at Chinese New Year’s for prosperity. A collection of meanings accumulated over the years, woven carefully into dishes that find themselves sustained by these stories, validated and made valuable by this history.

I hoard these meanings in the palm of my hand, gripping them close when I find them as if they are some token of belonging, a secret key to being a member of this culture. I lift them from casual conversations, from lessons in textbooks and online cooking blogs, from teachers and parents and friends—knowledge from the collective imparted to the individual. These dishes and their meanings have wound their way so securely through the generations that they are integral to the culture; they survive because we hold these things in our hands like treasures, artifacts of traditions and stories passed gently from mother to child, bound by the muscle memory of dumplings folded and pots stirred.

We have watched these same dishes appear again and again in ghostly iterations down the generations, birthed from a single story and meaning, a central seed first planted within history. But as time passes, things change — evolution acts upon all things, even traditions. They’ve slowly morphed into something different. New practices have tacked onto the old recipes, making something that grows its own roots and its own right to be passed down.

Chinese take-out cradled in plastic bags, splintered chopsticks tucked into the corners. Cheese tea with boba sitting at the bottom. Fortune cookies with slips of paper teaching me Chinese words I cannot read, promising me success or love or prosperity.

It is strange and beautiful the way a dish can live longer than its consumption, how it can grow and evolve and become something fresh to the new generation while still remaining something known and treasured to the old. Chocolate tangyuan next to the red bean, ice cream mochi sitting beside the black sesame. A dish and its survival beyond a single life cycle, outliving its creators, feeding the descendants of those who first made it.

So this is how these dishes live on beyond their lifespans, forming a foundation of a cultural heritage so rich you can taste it. And so we do. At family gatherings, at restaurants, at holiday celebrations with our relatives spread around a circular table, we hold these dishes in our hands — these dishes created by those before us that will be eaten again by those who come after, something passed down for them to collect and hold and preserve.

Eating these dishes is not an act of destruction. It is an act of remembrance.

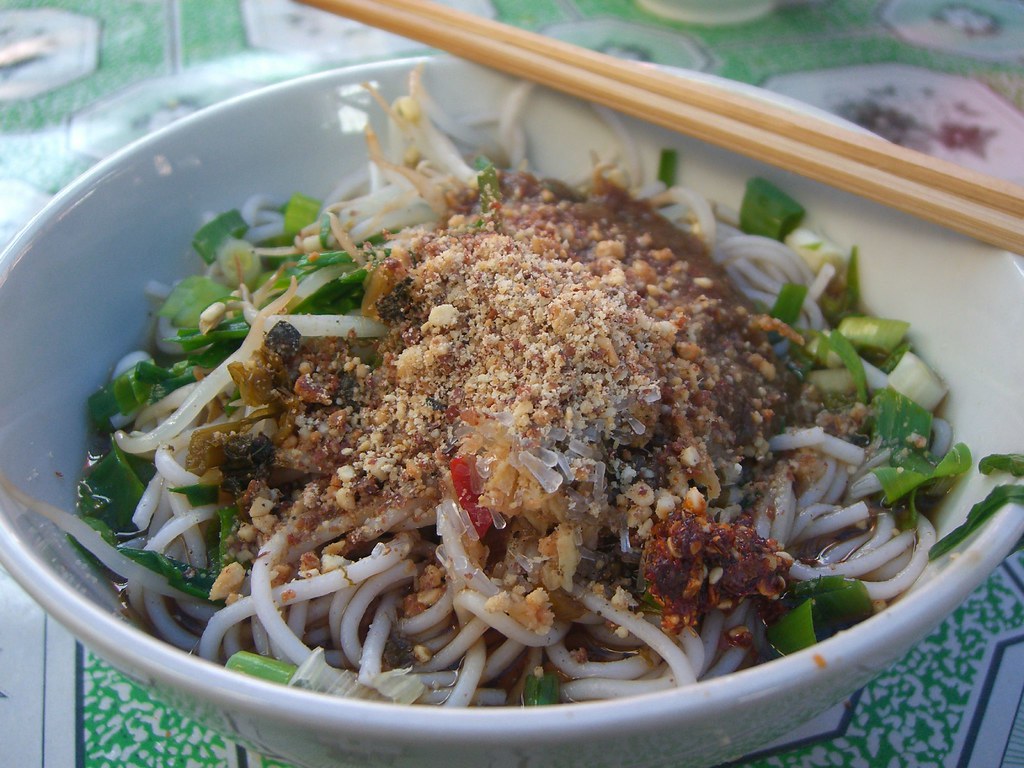

Featured image: “凉米线 Rice Noodles with Cold Spicy Garlic Sauce and Peanuts – Laomeng Market” by avlxyz is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Comments are closed.