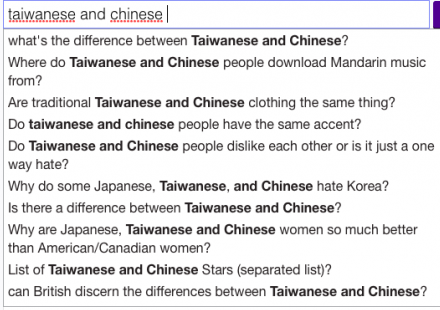

My mom is Taiwanese and my dad is Chinese, but many people only see me as Chinese. This was more of an issue when I was growing up than it is now, but usually when I tell someone in the U.S. that I’m Taiwanese and Chinese, they reply with, “Oh, so you’re Chinese, right?”

As a child who did not know any better, I learned that it was simply easier for me to introduce myself as Chinese, and before long I identified as Chinese American.

It was not until I visited Taiwan at eighteen, met my extended Taiwanese family, and fell in love with the country and culture that I fully embraced my identity as Taiwanese.

In contrast, I do not have the same relationship with China or the Chinese side of my family. It was easy for me to “drop” my identity as Chinese and instead identify as a Taiwanese American.

In community college, one of my white professors was talking about the importance of recognizing multiple identities and asked for students with more than one race or ethnicity to share their identities. When I offered mine, she laughed at me in front of the class, asked me, “Aren’t they the same thing?,” before following up by telling me that she always thought I was Korean based on the way I look.

At 18, embracing my Taiwanese identity meant dropping my Chinese one. To me, China and Taiwan were different enough that I knew that one did not equal the other, but similar enough that I thought it would be redundant to mention both.

I held this “either/or approach” until a few years ago, when one of my best friends came back home for winter break and told me that she was, “done with halves.” She told me that she was going to start owning both her White and Chinese identities.

Being biracial/biethnic does not equate to simply being “half-this” and “half-that,” because that implies that you aren’t wholly anything.

Whenever my friend told anyone that she was Asian, people would often tell her something along the lines of, “But you’re only half-Asian,” as if her identity as an Asian is something that they knew more about than her.

Identities are not fickle things to be discredited and taken away if the “math” doesn’t add up. It is due to my friend that I really began to think critically about what it means to have multiple identities and identified as both Taiwanese and Chinese.

In embracing both of my identities, I found that I had a new problem.

At conflict with my Chinese identity is my identity as Taiwanese.

Although I am no more Taiwanese than I am Chinese, I sometimes find myself thinking and acting as if I were not Chinese at all.

When I was visiting Taiwan last summer, I found myself picking up on the anti-mainland Chinese sentiment that people I was spending time with shared.

I began to feel annoyed by “those” rude Chinese tourists, as if I were not Chinese myself, and as though I was somehow better than them.

At other times, I found myself strongly identifying as Chinese. When I re-watched “Mulan” last weekend, I felt pride in the fact that a Disney heroine was Chinese.

Similarly, a few years ago, I learned that the first anti-immigration and anti-miscegenation laws in the United States were aimed at the Chinese, I felt pain and anger for my ancestors.

For me, part of self-care and self-love is awareness and acceptance of who I am. I do not want to only choose to identify as Chinese when it is advantageous and disown it where it is disadvantageous.

The question has moved beyond what I identify as to how to manage my identities.

China and Taiwan have been in conflict since the 40’s, so how can I reconcile these two identities and love for them both? Just because these two countries are in conflict with each other does not mean that my identities need to be that way.

Comments are closed.