For most crime novels, the story concludes at the trial. The swift blade of justice falls upon the condemned, and society exhales a collective sigh of relief. For us, tomorrow is another day — fresh sunlight warming the earth. But for the condemned, the story does not end; it merely pauses. Each day behind bars is a relentless repetition of the last, a sentence served in an endless loop. Paused until the prisoner either leaves or dies, society has deemed incarceration the only fitting narrative for the condemned.

But what if we looked beyond that narrative? What if we sought to understand the lives behind the labels — their struggles, their regrets, their voices? Today, I ask you to see incarceration not as a distant fate reserved for “others,” but as a human experience that deserves recognition and reflection, in particular for those within the Asian American community.

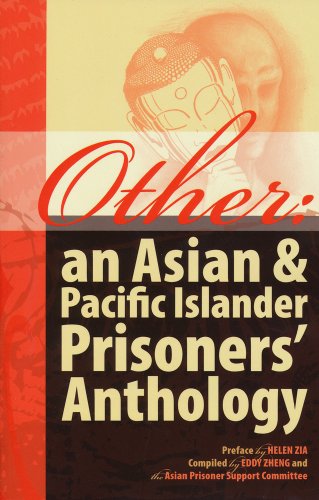

Beneath the street slang and hardened facades are hearts of loyal, remorseful children — aware of the homes and homelands they left behind. Many carry a deep understanding of the Asian American experience, and when given the opportunity, they have created powerful works of literature. In 2007, “Other: An Asian & Pacific Islander Prisoners’ Anthology” was published — a testament to years of writing submitted by Asian American prisoners across the country and compiled by the Asian Prisoner Support Committee. The anthology takes its name from the way API prisoners are often categorized as “Other,” a label that reflects the systemic neglect they face in society. The collection is divided into four sections, each exploring a different facet of the prisoners’ identities. Within these sections, a variety of literary styles emerge, shaping a raw and profound narrative of reflections, culture and resilience. Here I will share some of the writings I found interesting, which may inspire you to investigate them as well.

“From Cambodia with Peace”

The very first piece within the anthology is titled “From Cambodia with Peace.” The story is told in a linear fashion; specifically, the author Ryan Hem discusses the impact of war and prison on his family experience. He was without family when the Khmer Rouge took over; when in prison, he was also without family. Like a Buddhist monk, he left behind all worldly possessions when he entered prison. It is there that he saw through the karmic cycles and the suffering they cause. Rem accepted this as he was deported to Cambodia. Despite being materially impoverished, he found deeper fulfillment in the connections he rekindled and the family he discovered. Rem was able to call his father again; he is also a husband and a father. In a way, it is fitting that this story opens the anthology. The loss of family is one of the most devastating aspects of incarceration, and prisons are designed to sever these bonds. Unlike Hem, not all prisoners are fortunate enough to preserve them.

“A Day in the Life”

The relationship with family can be complex — its impact rippling across generations in ways difficult to measure. “A Day in the Life,” written by Viet Mike Ngo, predates “The Sympathizer,” arguably making Ngo a pioneer of spy fiction covering the Vietnam War. As the title suggests, Ngo’s story follows a single day. He juxtaposes the brutal, dog-eat-dog world of street violence and military warfare with the sterile monotony of prison life. His writing is notably dense, his sentences intricate and his word choice precise. The story blends philosophical musings, personal monologues, historical recounting and dark humor. At its core, it wrestles with identity — how an Asian man is never seen as a whole person, only as fragments shaped by the expectations of those around him. The ending is deliberately ambiguous: Is it a critique of toxic masculinity, showing that men (regardless of time or uniform) succumb to the same primal instincts? Or is it a meditation on fate — on the idea that karma is inescapable, and that he is not just paying for his own crimes but for those of his own soldiering father?

“Lessons Learned in Prison College”

Ngo also contributed several other works to the anthology, with his later pieces centering on his revolutionary ideals and deep connection to Vietnam. Among them, my personal favorite is “Lessons Learned in Prison College.” Here, he recounts the struggle of petitioning prison authorities to democratize the prison college — only to face brutal retaliation. With sharp conciseness and professional precision, Ngo laid bare the contradictions of a system that preaches rehabilitation while crushing any effort toward meaningful reform. Beneath the bureaucratic language lies a machine of oppression, built not for justice, but for control. This theme reverberates throughout the anthology. From arbitrary punishments handed out at random to the violent suppression of hunger strikes — where prison authorities in New Jersey physically assaulted starving Muslim protesters — the stories paint a harrowing picture of injustice behind the very walls meant to uphold it. These crimes remain largely unnoticed by the media, drowned out by government-fueled crises abroad. Muslim Americans, locked away in the name of homeland security, have spent years trapped in the prison system — beaten, silenced and forgotten. Several stories focus upon the fear of deportation, something which even the most evil of American criminals (like Ted Bundy) did not face. This is because our government views citizenship not as something inalienable and sacred, but as a tool to intimidate and control immigrants. Apart from the inherent danger, violence and injustice of prison life, one theme emerged repeatedly in the anthology — one that surprised me in its universality: love.

This is because our government views citizenship not as something inalienable and sacred, but as a tool to intimidate and control immigrants.

Many of the writings are love poems — dedicated to lovers, family and the forgotten. They reflect on estranged relatives, the shame they brought upon their families, the faces of lost lovers and the unexpected relationships forged in prison. Many prisoners ended up behind bars because, as children, the only love and support they could find was within gangs. Incarceration only further severs their ties to their birth communities. For some, like Peaches, an Asian drag queen compared to the famous actress Zhang Ziyi, prison was just a step in her journey of self-love. Escaping from an abusive family that did not accept her sexual identity, Peaches found the navigation of prison life to be a new experience. Here, she discovered a form of acceptance, where her femininity was valued. Her companionship was respected by the men around her, defying her conviction that “all prison men are evil.” These are all stories that stray far, far away from the norm of the model minority myth. Peaches and other Asian Americans impacted by incarceration cannot be denied their existence; it is imperative that we continue to share their stories.

Dehumanized, hidden and often shunned by society and their own families, Asian and Pacific Islander prisoners exist in a silence imposed upon them. Even within the broader Asian American community, already marginalized in many ways, they are the most invisible. The model minority myth casts a long shadow, one that erases those who do not fit its narrow mold. To acknowledge incarcerated Asian Americans is to disrupt the illusion of quiet success — to admit that our community, like any other, has its struggles. So, they remain unseen — not because they do not exist, but because their existence is inconvenient to the upholding of the model minority myth.

. The model minority myth casts a long shadow, one that erases those who do not fit its narrow mold. To acknowledge incarcerated Asian Americans is to disrupt the illusion of quiet success — to admit that our community, like any other, has its struggles.

Suppressed history is history doomed to repeat itself. As mentioned earlier, many incarcerated Asian Americans face the looming threat of deportation — a punishment eerily reminiscent of forced exile from medieval times. But this isn’t ancient history; it is happening right now.

In 2025, Ma Yang, a single mother of five, was deported to Laos after serving 30 months in federal prison for cannabis-related charges. An Hmong American refugee born in Thailand and raised entirely in America, Yang had permanent residency — until it was revoked under the Trump administration. In February, she was detained at an ICE facility in Milwaukee, then deported to Laos, a country she had never called home. Legal experts predict she may not return until the 2040s.

In the flood of shocking headlines since Trumps’ inauguration, stories like Ma Yang’s barely register — a mere drop in the avalanche of history. But a single drop is enough to destroy a life, to uproot a family and to shatter a community. How many drops will it take before the dignity and success that our community prizes are completely erased? We can dismiss these cases as exceptions to an unusual time, but how many “unusual times” must we endure before we begin to see the reality of injustice?

History has shown, time and again, that destruction of settled Asian communities is not an unfortunate accident, but a recurring story, one tolerated and even sponsored by the government. The burning of San Jose’s Chinatown in 1871. The mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The deportation of Asian Americans today who have only ever known this country as home, cast away in disproportionate punishments simply because they were not born here. These are not separate tragedies; they are echoes of the same narrative, told over and over again.

We remain perpetual foreigners in a nation we have helped build, struggling to find our place in its history. We are not powerless. We must confront these injustices, amplify the voices that have been silenced and refuse to let our own communities be torn apart by draconian authorities. Help those around you, be compassionate and try to act with love. In prison, education is a luxury, which many have suffered years to gain and maintain access to.

Include this piece in your education: This is no time to pause.

Consider reading the APSC’s second publication, “Arriving: Freedom Writings by Asian and Pacific Islanders Behind and Beyond Bars,” released in 2024.

Visual Credit: Asian Prisoner Support Committee and Joy Liu

Comments are closed.