Three years ago in my high school classroom, I watched as a college student mocked an entire language in the halls of my future university. My 11th-grade teacher projected the video for the whole class to see, the audio loud enough that the words rang through our minds. We talked about the way she condensed Asian languages into a caricature of themselves, reducing the breadth of a rich phonetic library into the space of six words, a sing-songy mockery spoken with the rhythm of a nursery rhyme.

“Ching chong ting tong ling long.”

Looking at those words, I can’t quite understand what they are supposed to tell me. I think I have been aware of them all my life, these words and this rhyme, but I scan through my limited knowledge of Mandarin and come up with no direct translation. It is an incoherent phrase in the language it is meant to imitate, only deriving meaning through the context of its use: when it is sounded out with taunting tones, a phrase targeted at a population and used as a mockery.

This saying has been used throughout history — an oversimplified, inaccurate representation of a nuanced and beautiful language. It has been tucked into the lyrics of taunting songs and schoolyard rhymes like a bad inside joke. For Asian Americans, these words widen the gap between “us” and “them,” separating the identities of “Asian” and “American.” By doing so, it casts us back into the role of the perpetual foreigner — people pin these words to our identities as if this is the only way we can speak, our fluency in English stolen from us with this assumption.

Every time I think this phrase has been buried in the distant past, a mistake made by prior generations, it crops back up in the present to remind me of the stereotypes associated with our race. When people think of Asians in connection with these words, it creates the sense that we can never be fluent in English and never belong here the way others do, our words forever jumbled in some fake foreign tongue. From schoolyard children to 20th century songwriters to a UCLA student sitting in a library, the use of this term has been a constant reminder of being “othered.” Asian Americans grow up hearing those words and knowing what they truly mean, learning to watch over our shoulders for those who try to deny us belonging within our own country.

In order to build diverse and inclusive communities, it is important to recognize the significance of the language used to refer to groups, especially those perceived as “other.” Though I was shocked three years ago to hear that this phrase was used at UCLA, a college campus I would soon call home, I have also been heartened to find myself in communities that acknowledge issues like this and seek to cultivate belonging. In my time on campus, I have been lucky enough to feel accepted as clubs and classes open up the conversation on discrimination — any annoyed looks at people in the library have been based on the loudness of their conversations, not the language of their speech.

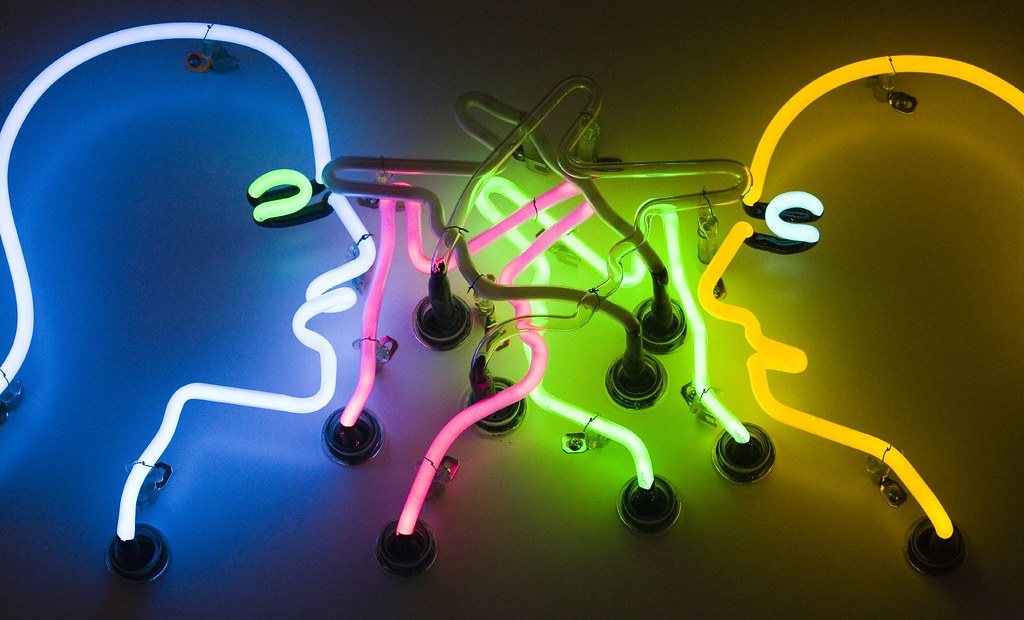

Featured image: “Language” by Thomas Hawk

Comments are closed.