In honor of May being Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, Pacific Ties and Asian Pacific Coalition (APC) are teaming up to featuring Asian Pacific Islander Desi American (APIDA) Bruins. We’ll be posting one interview per day.

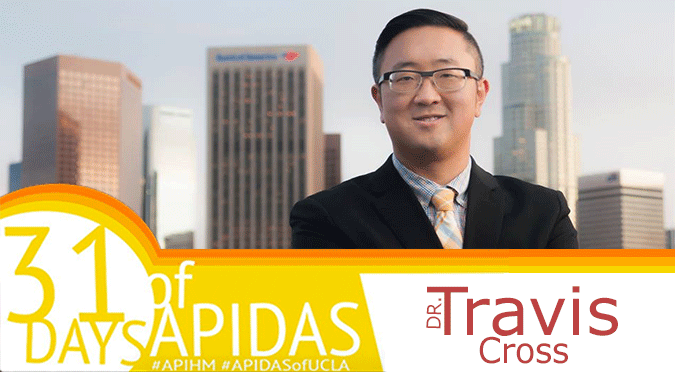

Dr. Travis J. Cross is Associate Professor of Music and department Vice Chair at UCLA, where he conducts the Wind Ensemble and Symphonic Band and directs the graduate program in wind conducting. Prior to UCLA, he was wind ensemble conductor at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Va. for five years. Full bio here.

Just to start off, do you want to talk a little bit about how you identify [as an APIDA] and what that means to you?

Well, I was born in Korea, but I was adopted. So I came to the United States when I was four months old, and I grew up in a Midwestern home with two Caucasian parents. My racial identity has been very apparent – and there were maybe five or ten Asians in the town where I lived in (Ankeny, Iowa, a suburb of Des Moines). So my racial identity was clear. But culturally, I didn’t have a whole lot of connection to any sort of Asian culture. My parents were part of an international adoption group – Iowans for International Adoption. And they would do a week-long Korean culture camp. It started out as a picnic, then it became a weekend retreat, and ultimately became the camp. This is up in Cedar Falls, about two hours from where I grew up

Was this with other Korean-American adoptees or international adoptees?

The kids in the camp are adoptees. The teaching staff was a group called the KIM staff (Korean Identity Matters), and they were initially the second generation Koreans – college age, little older than college age – and most of them were either from UC Berkeley or the University of Michigan. So they came in initially for the weekend retreat, then we kind of added the camp. And then we transitioned when I was in high school, or when I was just starting college, from them running the camp to our older, college-aged adoptees running the camp. We had been around long enough, we understood enough about it, we had enough connections, and it changed from a Korean culture camp to something we called KAMP, which stood for Korean Adoption Means Pride. So the focus would be on crafts and cooking and dress up and turtle boats and hangul and all kinds of that stuff, but also the adoptee experience, which we thought wasn’t really getting enough attention from the second-generation college-age Koreans who were leading the camp.

That was a really important part of my growth and my childhood because my parents weren’t afraid of that— it’s not like I was going to be fooled into thinking I was white. So they fostered kind of an appreciation in me and my sister in the Korean side of our background.

This is awesome: I was guest conducting in Korea last year, and the hotel that they put me up in was literally a five minute walk from the headquarters of the adoption agency, and so I actually walked to the agency–it was Sunday, so it was closed–and go in the lobby and see the building, so that was kind of fun. So my experience is a Midwestern upbringing, the adoptee experience, and the Korean racial experience.

What do you mean by the “Korean racial experience”?

Well, like, most people look at me and don’t think, “Oh I bet he’s adopted.” They just think, “there’s an Asian.”

Is it the perception from other people?

Yeah. And I think of myself as more Asian, now that I’m around more Asians. There was a time–I think it was in Virginia–when I was like, I don’t remember the exact circumstance, but I think I went into some engineering building at Virginia Tech, and I walked through the hallways and all the little offices were filled with these Chinese graduate students and I remember thinking in my head, “I am the only white person here.” And then I was like, “Wait a minute…”

There is nothing about my upbringing that is culturally Asian besides that when people look at me, that’s the first thing they see. So I have had to deal with some of the prejudice and some of the stereotypes and the racism at times: I’ve been called a “chink” and I’ve been asked if someone could blindfold me with dental floss…there’s all that kind of stuff. But I haven’t had the experience of being part of an Asian family.

What’s your experience as an Asian-American musician?

There are people who have told me throughout my entire life as a musician (not as much recently) that they’re surprised that I can be expressive because I’m Asian.

Really?

Because [people think] Asians are really, really technical and don’t have a lot of push and pull [to their music]. So that’s actually a thing; that’s an assumption that people make.

One of the things I enjoy about being here [at UCLA] is that I have the potential to be a role model for people who don’t often see someone who looks like me doing what I do. When I go do an honor band in California and half or two-thirds of the group is Asian, and they all seem surprised to actually see an Asian on the podium because even in California there aren’t a lot of [Asian] band directors–there are orchestra directors, violinists, and pianists [who are Asian], but there aren’t a lot of band directors [who are Asian]. And I hear them whispering, “He’s Asian.” And I think there’s value and meaning to that. (I hope I’m a good role model for white people too.) But that resonance is meaningful.

I don’t think of myself as an “Asian musician.” There’s nothing inherently Asian about my music-making. There is a lot that’s very American about it because that’s my cultural identity.

I feel the same way. I feel that sometimes, there’s this pressure to make “cultural” music because one looks a certain way, but that’s not my experience–that’s not what I’m trained to do as a classical musician, nor is it what I’m trying to do.

I mean, you want to have it both ways, and I think that’s okay. There are certain people in the political environment who say you can’t say that you’re proud of your race and then demand that you be treated equally. But I think you can. I think you can demand to be treated equally and fairly, but then when people say “I don’t see you as Asian,” which my friends in high school would say all the time, well, I am. It’s not the defining characteristic of my life–I don’t wake up and think, “Okay, I’m going to have an Asian day and go have some Asian breakfast and take an Asian shower.” I mean, it’s not like that, but I am Asian. So to say I don’t think of that, well, that’s part of who I am–it’s a lovely part of who I am.

Do you feel that between your time in the Midwest and Virginia and here in LA, have that experience shaped how you feel about your Asian identity?

I enjoy being around a lot of people that look like me. And this is a little trivial, but one of the things I find so interesting here is that there’s different kinds of Asian. Because of course! They’re going to be different people. But when you’re in a small place where there’s only a few, and you or those people happen to fit that stereotype, you just assume that everyone plays the clarinet and is good at math. So that’s been interesting.

People find strength in groups, and seeing people who look like them and act like them and dress like them, you know, you don’t want to be too insular, but you there’s nothing wrong with taking strength in sharing experiences you share.

What are some of your upcoming projects?

I wrote a couple pieces this winter/spring, and I have a couple more that I have to write over the summer. So I’ll be doing a little bit of writing music this summer. Most of my projects are guest conducting. You know, going somewhere for a weekend to conduct a band or from time to time going abroad for a week. I’m actually going to go to Singapore this fall for a week of teaching and conducting there, which I rather enjoy. Since I came over at the age of four months, I have not been to Asia that many times.

Last summer I was out a lot. This summer all I have is the our conducting workshop, and I’m going to do a week at the International Music Camp, and otherwise I’ll be home. I look forward to finally getting my apartment totally unpacked and catching up on email, and going to a lot of Hollywood Bowl concerts, and going to some Dodger games, and doing a lot of stuff for school. As you know, we’ve got a lot of big changes [with the music school becoming its own school] and trying to figure out how to be the best school we can be. And writing music.

Anything else? Why do you do music?

The skills you build from practicing, being in a studio, being in an ensemble, learning a language like music theory–that all will serve you. Music is like football, where most people who do it at the college level don’t do it professionally. I’d assume that for most college football players, playing football is more important than anything they’re doing for their major; they are majoring in football: football performance, football composition, football education, whatever. But they’re learning about who they are and developing skills of working with people that they can use to be a reporter or work in an office (e.g. arts management). If you major in music and decide not to pursue a career performing music, you haven’t wasted your time. You’ve built all kinds of skills that will be valuable to employers in all these different ways.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Check out Asian Pacific Coalition’s new website!

Comments are closed.